|

Anal

Cancer Anal cancer, an uncommon

cancer, is a disease in which malignant cells are found in the anus. The anus is

the opening at the end of the rectum (the end part of the large intestine)

through which body waste passes. Cancer in the outer part of the anus is more

likely to occur in men; cancer of the inner part of the rectum (anal canal) is

more likely to occur in women. If your anus is often red, swollen, and sore, you

have a greater chance of getting anal cancer. Tumours found in the area of skin

with hair on it just outside the anus are skin tumours, not anal cancer.

Like most cancers, anal cancer

is best treated when it is found early. You should see your doctor if you have

one or more of the following symptoms: bleeding from the rectum (even a small

amount), pain or pressure in the area around the anus, itching or discharge from

the anus, or a lump near the anus. Like most cancers, anal cancer

is best treated when it is found early. You should see your doctor if you have

one or more of the following symptoms: bleeding from the rectum (even a small

amount), pain or pressure in the area around the anus, itching or discharge from

the anus, or a lump near the anus.

If you have signs of cancer,

your doctor will usually examine the outside part of the anus and give you a

rectal examination. In a rectal examination, your doctor, wearing thin gloves,

puts a greased finger into the rectum and gently feels for lumps. Your doctor

may also check any material on the glove to see if there is blood in it. If you

feel pain when touched in the anal area, your doctor may give you medicine to

put you to sleep (general anaesthesia) in order to continue the examination.

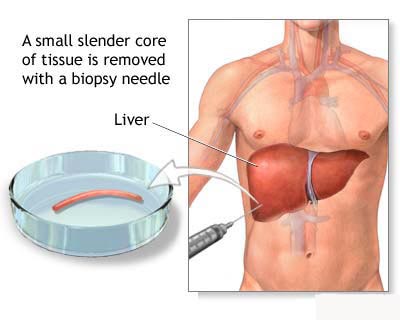

Your doctor may cut out a small piece of tissue and look at it under a

microscope to see if there are any cancer cells. This procedure is called a

biopsy.

Your prognosis (chance of

recovery) and choice of treatment depend on the stage of your cancer (whether it

is just in the anus or has spread to other places in the body) and your general

state of health.

Stages Of Anal Cancer

Once anal cancer is found

(diagnosed), more tests will be done to find out if cancer cells have spread to

other parts of the body. This testing is called staging. To plan treatment, your

doctor needs to know the stage of your disease. The following stages are used

for anal cancer.

Stage 0 Or Carcinoma In Situ

Stage 0 anal cancer is very early cancer. The cancer is found only in the

top layer of anal tissue.

Stage I The cancer has

spread beyond the top layer of anal tissue and is smaller than 2 centimetres

(less than 1 inch).

Stage II Cancer has

spread beyond the top layer of anal tissue and is larger than 2 centimetres

(about 1 inch), but it has not spread to nearby organs or lymph nodes. (Lymph

nodes are small, bean-shaped structures found throughout the body. They produce

and store infection-fighting cells.)

Stage IIIA Cancer

has spread to the lymph nodes around the rectum or to nearby organs such as the

vagina or bladder.

Stage IIIB Cancer has

spread to the lymph nodes in the middle of the abdomen or in the groin, or the

cancer has spread to both nearby organs and the lymph nodes around the rectum.

Stage IV Cancer has

spread to distant lymph nodes within the abdomen or to organs in other parts of

the body.

Recurrent Recurrent

disease means that the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has been

treated. It may come back in the anus or in another part of the body.

How Anal Cancer Is

Treated

There are treatments for all

patients with anal cancer. Three kinds of treatment are used: surgery (taking

out the cancer in an operation) radiation therapy (using high-dose x-rays or

other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells) chemotherapy (using drugs to kill

cancer cells).

Surgery is a common way to

diagnose and treat anal cancer. Your doctor may take out the cancer using one of

the following methods:

Local resection is an operation

that takes out only the cancer. Often the ring of muscle around the anus that

opens and closes it (the sphincter muscle) can be saved during surgery so that

you will be able to pass your body wastes as before.

Abdominoperineal resection

is

an operation in which the doctor removes the anus and the lower part of the

rectum by cutting into the abdomen and the perineum, which is the space between

the anus and the scrotum (in men) or the anus and the vulva (in women). Your

doctor will then make an opening (stoma) on the outside of the body for waste to

pass out of the body. This opening is called a colostomy. Although this

operation was once commonly used for anal cancer, it is not used as much today

because radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy is an equally effective

treatment option but does not require a colostomy. If you have a colostomy, you

will need to wear a special bag to collect body wastes. This bag, which sticks

to the skin around the stoma with a special glue, can be thrown away after it is

used. This bag does not show under clothing, and most is

an operation in which the doctor removes the anus and the lower part of the

rectum by cutting into the abdomen and the perineum, which is the space between

the anus and the scrotum (in men) or the anus and the vulva (in women). Your

doctor will then make an opening (stoma) on the outside of the body for waste to

pass out of the body. This opening is called a colostomy. Although this

operation was once commonly used for anal cancer, it is not used as much today

because radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy is an equally effective

treatment option but does not require a colostomy. If you have a colostomy, you

will need to wear a special bag to collect body wastes. This bag, which sticks

to the skin around the stoma with a special glue, can be thrown away after it is

used. This bag does not show under clothing, and most

people

take care of these bags themselves. Lymph nodes may also be taken out at the

same time or in a separate operation (lymph node dissection). people

take care of these bags themselves. Lymph nodes may also be taken out at the

same time or in a separate operation (lymph node dissection).

Radiation therapy uses x-rays

or other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumours. Radiation may

come from a machine outside the body (external radiation therapy) or from

putting materials that produce radiation (radioisotopes) through thin plastic

tubes in the area where the cancer cells are found (internal radiation therapy).

Radiation can be used alone or in addition to other treatments.

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill

cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be taken by pill, or it may be put into the body

by a needle in a vein or muscle. Chemotherapy is called a systemic treatment

because the drugs enter the bloodstream, travel through the body, and can kill

cancer cells throughout the body. Some chemotherapy drugs can also make cancer

cells more sensitive to radiation therapy. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy

can be used together to shrink tumours and make an abdominoperineal resection

unnecessary. When only limited surgery is required, the sphincter muscle can

often be saved.

STAGE 0 ANAL CANCER

Your treatment will probably be

local resection.

STAGE I ANAL CANCER

Your treatment may be one of

the following: 1. Local resection (for some small tumours). 2. External radiation

therapy with chemotherapy. Some patients may also receive internal radiation

therapy. 3. If cancer cells remain following therapy, you may need surgery of

the anal canal to remove the cancer.

STAGE II ANAL CANCER

Your treatment may be one of

the following: 1. Local resection (for small tumours). 2. External radiation

therapy with chemotherapy. Some patients may also receive internal radiation

therapy. 3. If cancer cells remain following therapy, you may need surgery of

the anal canal to remove the cancer.

STAGE IIIA ANAL CANCER

Your treatment may be one of

the following: 1. Radiation therapy with chemotherapy. 2. Surgery. Depending on

how much cancer remains following chemotherapy and radiation, local resection or

surgery to remove cancer in the anal canal may be done. 3. Clinical trials of

surgery (resection) followed by external radiation therapy. 4. Clinical trials

of surgery followed by chemotherapy if chemotherapy has not been used prior to

surgery.

STAGE IIIB ANAL CANCER

Your treatment will probably be

radiation therapy and chemotherapy followed by surgery. Depending on how much

cancer remains following chemotherapy and radiation, local resection or surgery

to remove the anus and the lower part of the rectum (abdominoperineal resection)

may be done. During surgery, the lymph nodes in the groin may be removed (lymph

node dissection).

STAGE IV ANAL CANCER

Your treatment may be one of

the following:

1. Surgery to relieve symptoms

2. Radiation therapy to relieve

symptoms

3. Chemotherapy and radiation

therapy to relieve symptoms

4. Clinical trials

BACK

|

|

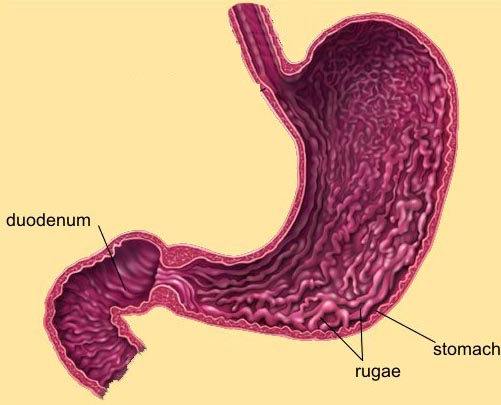

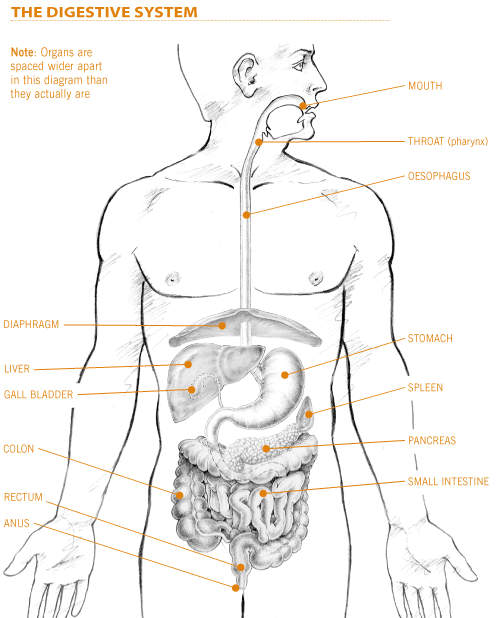

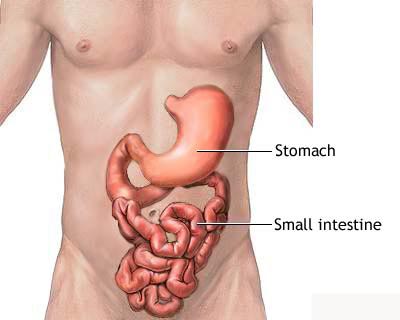

Stomach

(Gastric) Cancer

Gastric cancer is a disease in which malignant

cells form in the lining of the stomach.

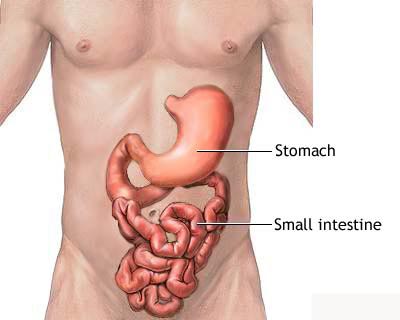

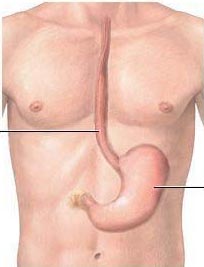

The

stomach is a J-shaped organ in the upper abdomen. It is part of the digestive

system, which processes nutrients (vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats,

proteins, and water) in foods that are eaten and helps pass waste material out

of the body. Food moves from the throat to the stomach through a hollow,

muscular tube called the oesophagus. After leaving the stomach, partly-digested

food passes into the small intestine and then into the large intestine (the

colon). The

stomach is a J-shaped organ in the upper abdomen. It is part of the digestive

system, which processes nutrients (vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats,

proteins, and water) in foods that are eaten and helps pass waste material out

of the body. Food moves from the throat to the stomach through a hollow,

muscular tube called the oesophagus. After leaving the stomach, partly-digested

food passes into the small intestine and then into the large intestine (the

colon).

The wall of the stomach is made up of 3 layers of tissue: the mucosal

(innermost) layer, the muscularis (middle) layer, and the serosal (outermost)

layer. Gastric cancer begins in the cells lining the mucosal layer and spreads

through the outer layers as it grows.

Stromal tumours of the stomach begin in supporting connective tissue and are

treated differently from gastric cancer.

Age, diet, and stomach disease can affect the risk of developing gastric cancer.

Risk factors include the following:

- Helicobacter pylori infection of the

stomach.

- Chronic gastritis (inflammation of the

stomach).

- Older age.

- Being male.

- A diet high in salted, smoked, or poorly

preserved foods and low in fruits and vegetables.

- Pernicious anaemia.

- Smoking cigarettes.

- Intestinal metaplasia.

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or

gastric polyps.

- A mother, father, sister, or brother who

has had stomach cancer.

Possible signs of gastric cancer include

indigestion and stomach discomfort or pain. These and other symptoms may be caused by gastric cancer or by other conditions. In the early stages of gastric cancer, the following symptoms may occur:

- Indigestion and stomach

discomfort

- A bloated feeling after

eating

- Mild nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Heartburn

In more advanced stages of gastric cancer, the

following symptoms may occur:

- Blood in the stool

- Vomiting

- Weight loss

(unexplained)

- Stomach pain

- Jaundice (yellowing of

eyes and skin)

- Ascites (build-up of

fluid in the abdomen)

- Difficulty swallowing

A doctor should be consulted if any of these problems occur.

Tests that examine the stomach and oesophagus are used to detect (find) and

diagnose gastric cancer.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

Physical exam and history: An exam of the body to check general signs of

health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else

that seems unusual. A history of the patientís health habits and past illnesses

and treatments will also be taken.

Blood chemistry studies: A procedure in

which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain substances

released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual (higher or

lower than normal) amount of a substance can be a sign of disease in the organ

or tissue that produces it.

Complete blood count: A procedure in

which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

The number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

The amount of haemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood

cells.

The portion of the sample made up of red blood cells.

Upper endoscopy: A procedure to look

inside the oesophagus, stomach, and duodenum (first part of the small intestine)

to check for abnormal areas. An endoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is passed

through the mouth and down the throat into the oesophagus.

Faecal occult blood test: A test to

check stool (solid waste) for blood that can only be seen with a microscope.

Small samples of stool are placed on special cards and returned to the doctor or

laboratory for testing.

Barium swallow: A series of x-rays of

the oesophagus and stomach. The patient drinks a liquid that contains barium (a

silver-white metallic compound). The liquid coats the oesophagus and stomach and

x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called an upper GI series.

Biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues

so they can be viewed under a microscope to check for signs of cancer. A biopsy

of the stomach is usually done during the endoscopy.

CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that

makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from

different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray

machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or

tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography,

computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

Certain factors affect treatment options and

prognosis (chance of recovery).

The treatment options and prognosis (chance of recovery) depend on the stage and

extent of the cancer (whether it is in the stomach only or has spread to lymph

nodes or other places in the body) and the patientís general health.

After gastric cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer

cells have spread within the stomach or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the stomach or to other

parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging

process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage

in order to plan the best treatment.

The following tests and procedures may be used in the staging process:

ŖHCG (beta human chorionic gonadotropin), CA-125, and CEA (carcinoembryonic

antigen) assays: Tests that measure the levels of ŖHCG, CA-125, and CEA in

the blood. These substances are released into the bloodstream from both cancer

cells and normal cells. When found in higher than normal amounts, they can be a

sign of gastric cancer or other conditions.

Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and

bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through

the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): A

procedure in which an endoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted into the

body. The endoscope is used to bounce high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off

internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body

tissues called a sonogram. This procedure is also called endosonography.

CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that

makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from

different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray

machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or

tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography,

computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

Laparoscopy: A surgical procedure to

look at the organs inside the abdomen to check for abnormal areas. An incision

(cut) is made in the abdominal wall and a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is

inserted into the abdomen. Tissue samples and lymph nodes may be removed for

biopsy.

PET scan (positron emission tomography

scan): A procedure to find malignant tumour cells in the body. A small

amount of radionuclide glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner

rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in

the body. Malignant tumour cells show up brighter in the picture because they

are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells.

The following stages are used for gastric

cancer:

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

In stage 0, cancer is found only in the inside lining of the mucosal (innermost)

layer of the stomach wall. Stage 0 is also called carcinoma in situ.

Stage I

Stage I gastric cancer is divided into stage IA and stage IB, depending on where

the cancer has spread.

Stage IA: Cancer has spread completely through the mucosal (innermost) layer of

the stomach wall.

Stage IB: Cancer has spread: completely through the mucosal (innermost) layer of

the stomach wall and is found in up to 6 lymph nodes near the tumour; or to the

muscularis (middle) layer of the stomach wall.

Stage II

In stage II gastric cancer, cancer has spread: completely through the mucosal

(innermost) layer of the stomach wall and is found in 7 to 15 lymph nodes near

the tumour; or to the muscularis (middle) layer of the stomach wall and is found

in up to 6 lymph nodes near the tumour; or to the serosal (outermost) layer of

the stomach wall but not to lymph nodes or other organs.

Stage III

Stage III gastric cancer is divided into stage IIIA and stage IIIB depending on

where the cancer has spread.

Stage IIIA: Cancer has spread to:

the muscularis (middle) layer of the stomach wall and is found in 7 to 15 lymph

nodes near the tumour; or the serosal (outermost) layer of the stomach wall and

is found in 1 to 6 lymph nodes near the tumour; or organs next to the stomach

but not to lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

Stage IIIB: Cancer has spread to the serosal (outermost) layer of the stomach

wall and is found in 7 to 15 lymph nodes near the tumour.

Stage IV

In stage IV, cancer has spread to: organs next to the stomach and to at least

one lymph node; or more than 15 lymph nodes; or other parts of the body.

There are different types of treatment for

patients with gastric cancer

Different types of treatments are

available for patients with

gastric

cancer. Some treatments are standard (the currently

used treatment), and some are being tested in

clinical trials. Before starting treatment, patients

may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. A treatment clinical

trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain

information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials

show that a new treatment is better than the

"standard" treatment, the new treatment may become the

standard treatment.

Four types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery is a common

treatment of all stages of gastric cancer. The following types of surgery may be

used:

- Subtotal

gastrectomy: Removal of the part of the

stomach that contains cancer, nearby

lymph nodes, and parts of other

tissues and

organs near the

tumour. The

spleen may be removed. The spleen is an organ in the

upper

abdomen that filters the blood and removes old blood

cells.

- Total gastrectomy:

Removal of the entire stomach, nearby lymph nodes, and parts of the

oesophagus,

small intestine, and other tissues near the tumour.

The spleen may be removed. The oesophagus is connected to the small intestine

so the patient can continue to eat and swallow.

If the tumour is blocking the opening to the

stomach but the cancer cannot be completely removed by standard surgery, the

following procedures may be used:

-

Endoluminal stent placement: A procedure to insert a

stent (a thin, expandable tube) in order to keep a

passage (such as arteries or the oesophagus) open. For tumours blocking the

opening to the stomach, surgery may be done to place a stent from the

oesophagus to the stomach to allow the patient to eat normally.

- Endoscopic laser surgery:

A procedure in which an

endoscope (a thin, lighted tube) with a

laser attached is inserted into the body. A laser is

an intense beam of light that can be used as a knife.

-

Electrocautery: A procedure that uses an electrical

current to create heat. This is sometimes used to remove

lesions or control bleeding.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a

cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer

cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping the

cells from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or

injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the

bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic

chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly in

the spinal column, a body cavity such as the abdomen, or an organ, the drugs

mainly affect cancer cells in those areas. The way the chemotherapy is given

depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy

is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy

x-rays or other types of

radiation to kill cancer cells. There are two types of

radiation therapy.

External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the

body to send radiation toward the cancer.

Internal radiation therapy uses a

radioactive substance sealed in needles,

seeds, wires, or

catheters that are placed directly into or near the

cancer. The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of

the cancer being treated.

Chemoradiation

Chemoradiation combines chemotherapy and radiation therapy to increase the

effects of both. Chemoradiation treatment given after surgery to increase the

chances of a cure is called

adjuvant therapy. If it is given before surgery, it is

called

neoadjuvant therapy.

Other types of

treatment are being tested in clinical trials. These include the following:

Biologic therapy

Biologic therapy

is a treatment that uses the patientís

immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the

body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the bodyís

natural defences against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called

biotherapy or immunotherapy.

Treatment Options by Stage

Stage 0 Gastric Cancer (Carcinoma in Situ)

Treatment of stage 0 gastric cancer may include the following:

Surgery (total or subtotal gastrectomy).

Stage I and Stage II Gastric Cancer

Treatment of stage I and stage II gastric cancer may include the following:

Surgery (total or subtotal gastrectomy).

Surgery (total or subtotal gastrectomy) followed by chemoradiation therapy.

A clinical trial of chemoradiation therapy given before surgery.

Stage III Gastric Cancer

Treatment of stage III gastric cancer may include the following:

Surgery (total gastrectomy).

Surgery followed by chemoradiation therapy.

A clinical trial of chemoradiation therapy given before surgery.

Stage IV Gastric Cancer

Treatment of stage IV gastric cancer that has not spread to distant organs may

include the following:

Surgery (total gastrectomy) followed by chemoradiation therapy.

A clinical trial of chemoradiation therapy given before surgery.

Treatment of stage IV gastric cancer that has spread to distant organs may

include the following:

Chemotherapy as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve the quality

of life.

Endoscopic laser surgery or endoluminal stent placement as palliative therapy to

relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life.

Radiation therapy as palliative therapy to stop bleeding, relieve pain, or

shrink a tumour that is blocking the opening to the stomach.

Surgery as palliative therapy to stop bleeding or shrink a tumour that is

blocking the opening to the stomach.

Treatment Options for Recurrent Gastric Cancer

Treatment of recurrent gastric cancer may include the following:

Chemotherapy as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve the quality

of life.

Endoscopic laser surgery or electrocautery as palliative therapy to relieve

symptoms and improve the quality of life.

Radiation therapy as palliative therapy to stop bleeding, relieve pain, or

shrink a tumour that is blocking the stomach.

A clinical trial of new anticancer drugs or biologic therapy.

BACK

|

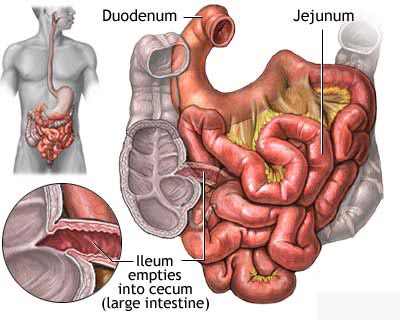

Small

Intestine Cancer

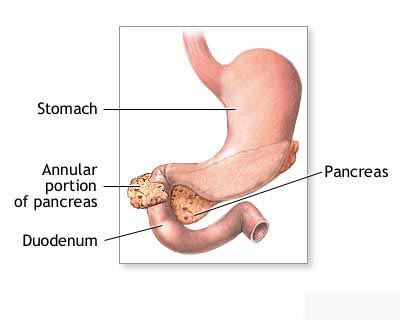

The

small intestine is the portion of the digestive system most responsible for

absorption of nutrients from food into the bloodstream. The pyloric sphincter

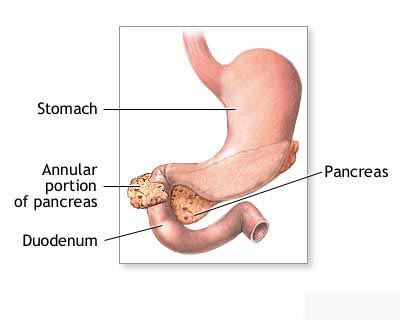

governs the passage of partly digested food from the stomach into the duodenum.

This short first portion of the small intestine is followed by the jejunum and

the ileum. The ileocecal valve of the ileum passes digested material into the

large intestine The

small intestine is the portion of the digestive system most responsible for

absorption of nutrients from food into the bloodstream. The pyloric sphincter

governs the passage of partly digested food from the stomach into the duodenum.

This short first portion of the small intestine is followed by the jejunum and

the ileum. The ileocecal valve of the ileum passes digested material into the

large intestineCancer of the small intestine, a rare cancer,

is a disease in which cancer cells are found in the tissues of the small

intestine. The small intestine is a long tube that folds many times to fit

inside the abdomen. It connects the stomach to the large intestine (bowel). In

the small intestine, food is broken down to remove vitamins, minerals, proteins,

carbohydrates, and fats.

A doctor should be seen if there are any of

the following:

- Pain or cramps in the middle of

the abdomen.

- Weight loss without dieting.

- A lump in the abdomen.

- Blood in the stool.

If there are symptoms, a doctor will usually

order an upper gastrointestinal x-ray (also called an upper GI series). For this

examination, a patient drinks a liquid containing barium, which makes the

stomach and intestine easier to see in the x-ray. This test is usually performed

in a doctorís office or in a hospital radiology department.

The doctor may also do a CT scan, a special

x-ray that uses a computer to make a picture of the inside of the abdomen. An

ultrasound, which uses sound waves to find tumours, or an MRI scan, which uses

magnetic waves to make a picture of the abdomen, may also be done.

The doctor may put a thin lighted tube called

an endoscope down the throat, through the stomach, and into the first part of

the small intestine. The doctor may cut out a small piece of tissue during the

endoscopy. This is called a biopsy. The tissue is then looked at under a

microscope to see if it contains cancer cells.

The chance of recovery (prognosis) depends on

the type of cancer, whether it is just in the small intestine or has spread to

other tissues, and the patientís overall health.

Stages of cancer of the small intestine

Once small intestine cancer is found, more tests will be done to find out if

cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body. Although there is a staging

system for cancer of the small intestine, for treatment purposes this cancer is

grouped based on what kind of cells are found. The types of cancer found in the

small intestine include adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, and carcinoid tumours.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma starts in the lining of the small intestine and is the most

common type of cancer of the small intestine. These tumours occur most often in

the part of the small intestine nearest the stomach. These cancers often grow

and block the bowel.

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcomas are cancers that start growing in the smooth muscle lining of

the small intestine.

Recurrent

Recurrent disease means that the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has

been treated. It may come back in the small intestine or in another part of the

body.

How cancer of the small intestine is

treated

There are treatments for all patients with

cancer of the small intestine. Three kinds of treatment are used:

- Surgery (taking out the

cancer).

- Radiation therapy (using

high-dose x-rays to kill cancer cells).

- Chemotherapy (using drugs to

kill cancer cells).

Surgery to remove the cancer is the most

common treatment. Lymph nodes in the area may also be removed and looked at

under a microscope to see if they contain cancer. If the tumour is large, a

doctor may cut out a section of the small intestine containing the cancer and

reconnect the intestine.

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays to

kill cancer cells and shrink tumours. Radiation may come from a machine outside

the body (external radiation therapy) or from putting materials that produce

radiation (radioisotopes) through thin plastic tubes in the area where the

cancer cells are found (internal radiation therapy). Drugs that make the cancer

cells more sensitive to radiation (radio sensitizers) are sometimes given along

with radiation. Radiation can be used alone or in addition to surgery and/or

chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells.

Chemotherapy may be taken by pill, or it may be put in the body through a needle

in a vein or muscle. Chemotherapy is called a systemic treatment because the

drug enters the bloodstream, travels through the body, and can kill cancer cells

outside the intestine.

If the doctor removes all the cancer that can

be seen at the time of the operation, the patient may be given chemotherapy

after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Chemotherapy given after

an operation is called adjuvant chemotherapy.

Biological therapy (using the bodyís immune

system to fight cancer) is being studied in clinical trials. Biological therapy

tries to get the body to fight cancer. It uses materials made by the body or

made in a laboratory to boost, direct, or restore the bodyís natural defences

against disease. Biological therapy is sometimes called biological response

modifier (BRM) therapy or immunotherapy.

Small Intestine Adenocarcinoma

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to cut out the tumour.

- Surgery to allow food in the

small intestine to go around the cancer (bypass) if the cancer cannot be

removed.

- Radiation therapy to relieve

symptoms.

- A clinical trial of radiation

plus drugs to make cancer cells more sensitive to radiation (radio

sensitizers), with or without chemotherapy.

- A clinical trial of

chemotherapy or biological therapy.

Small Intestine Leiomyosarcoma

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove the cancer.

- Surgery to allow food in the

small intestine to go around the cancer (bypass) if the cancer cannot be

removed.

- Radiation therapy.

- Surgery, chemotherapy, or

radiation therapy to relieve symptoms.

- A clinical trial of

chemotherapy or biological therapy.

Recurrent Small Intestine Cancer

If the cancer comes back in another part of

the body, treatment will probably be a clinical trial of chemotherapy or

biological therapy.

If the cancer has come back only in one area,

treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove the cancer.

- Radiation therapy or

chemotherapy to relieve symptoms.

- A clinical trial of radiation

with drugs to make the cancer cells more sensitive to radiation (radio

sensitizers), with or without chemotherapy.

BACK

|

|

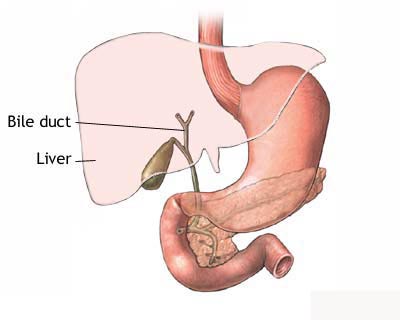

Bile Duct Cancer

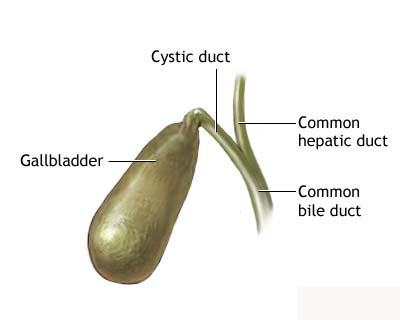

Extrahepatic bile duct cancer,

a rare cancer, is a disease in which malignant cells are found in the tissues of

the extrahepatic bile duct. The bile duct is a tube that connects the liver and

the gallbladder to the small intestine. The part of the bile duct that is

outside the liver is called the extrahepatic bile duct. A fluid called bile,

which is made by the liver and breaks down fats during digestion, is stored in

the gallbladder. When food is being broken down in the intestines, bile is

released from the gallbladder through the bile duct to the first part of the

small intestine.

A doctor should be seen if

there are any of the following symptoms:

Yellowing of the

skin (jaundice) Yellowing of the

skin (jaundice)

Pain in the

abdomen

Fever

Itching

If there are symptoms, a doctor

will perform an examination and order tests to see if there is cancer. A patient

may have an ultrasound, a test that uses sound waves to find tumours. A patient

may also have a CT (computed tomographic) scan, which is a special type of x-ray

that uses a computer to make a picture of the inside of the abdomen. Another

special scan called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses magnetic waves

to make a picture of the inside of the abdomen, may be done as well.

A doctor may perform a test

called an ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography). During this

test, a flexible tube is put down the throat, through the stomach, and into the

small intestine. The doctor can see through the tube and inject dye into the

drainage tube (duct) of the pancreas so that the area can be seen more clearly

on an x-ray.

PTC (percutaneous transhepatic

cholangiography) is another test that can help find cancer of the extrahepatic

bile duct. During this test, a thin needle is put into the liver through the

right side of the patient. Dye is injected through the needle into the bile duct

in the liver so that blockages can be seen on x-rays.

If tissue that is not normal is

found, the doctor may remove a small amount of fluid or tissue from the bile

duct and look at it under the microscope to see if there are any cancer cells.

This procedure is called a biopsy and is usually done during the PTC or ERCP.

Because it is sometimes hard to

tell whether a patient has cancer or another disease, surgery may be needed to

see if there is cancer of the bile duct. If this is the case, the doctor will

cut into the abdomen and look at the bile duct and the tissues around it for

cancer. If there is cancer and if it looks like it has not spread to other

tissues, the doctor may remove the cancer or relieve blockages caused by the

tumour.

The chance of recovery

(prognosis) and choice of treatment depends on the location of the cancer in the

bile duct, the stage of the cancer (whether it is only in the bile duct or has

spread to other places), and the patientís general health.

Stages of extrahepatic bile

duct cancer

Once extrahepatic bile duct

cancer is found (diagnosed), more tests will be done to find out if cancer cells

have spread to other parts of the body. This is called staging. To plan

treatment, a doctor needs to know the stage of the cancer. The following stages

are used for extrahepatic bile duct cancer:

Localized

The cancer is only in the area

where it began and can be removed in an operation.

Unresectable

All of the cancer cannot be

removed in an operation. The cancer may have spread to nearby organs and lymph

nodes or to other parts of the body. (Lymph nodes are small bean-shaped

structures that are found throughout the body. They produce and store

infection-fighting cells.)

Recurrent

Recurrent disease means that

the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has been treated. It may come back

in the bile duct or in another part of the body.

How extrahepatic bile duct

cancer is treated

There are treatments for all

patients with extrahepatic bile duct cancer. Two kinds of treatment are used:

- Surgery (taking

out the cancer or taking steps to relieve symptoms caused by the cancer)

- Radiation

therapy (using high-dose x-rays to kill cancer cells)

Other treatments for

extrahepatic bile duct cancer are being studied in clinical trials. These

include:

- Chemotherapy

(using drugs to kill cancer cells)

- Biological

therapy (using the bodyís immune system to fight cancer)

Surgery is a common treatment

of extrahepatic bile duct cancer. If the cancer is small and is only in the bile

duct, a doctor may remove the whole bile duct and make a new duct by connecting

the duct openings in the liver to the intestine. The doctor will also remove

lymph nodes and look at them under the microscope to see if they contain cancer.

If the cancer has spread outside the bile duct, a surgeon may remove the bile

duct and the tissues around it.

If the cancer has spread and it

cannot be removed, the doctor may do surgery to relieve symptoms. If the cancer

is blocking the small intestine and bile builds up in the gallbladder, the

doctor may do surgery to go around (bypass) all or part of the small intestine.

During this operation, the doctor will cut the gallbladder or bile duct and sew

it to the small intestine. This is called biliary bypass. Surgery or x-ray

procedures may also be done to put in a tube (catheter) to drain bile that has

built up in the area. During these procedures, the doctor may make the catheter

drain through a tube to the outside of the body or the catheter may go around

the blocked area and drain the bile to the small intestine. In addition, if the

cancer is blocking the flow of food from the stomach, the stomach may be sewn

directly to the small intestine so the patient can continue to eat normally.

Radiation therapy is the use of

high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumours. Radiation may come

from a machine outside the body (external-beam radiation therapy) or from

putting materials that produce radiation (radioisotopes) through thin plastic

tubes into the area where the cancer cells are found (internal radiation

therapy).

Chemotherapy is the use of

drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be taken by pill, or it may be put

into the body by inserting a needle into a vein or muscle. Chemotherapy is

called a systemic treatment because the drug enters the bloodstream, travels

through the body, and can kill cancer cells outside the bile duct.

Biological therapy tries to get

the body to fight cancer. It uses materials made by the body or made in a

laboratory to boost, direct, or restore the bodyís natural defences against

disease. Biological therapy is sometimes called biological response modifier (BRM)

therapy or immunotherapy. This treatment is currently only being given in

clinical trials.

Localized

Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer

Treatment may be one of the

following:

- Surgery to

remove the cancer.

- Surgery to

remove the cancer followed by external-beam radiation therapy.

Unresectable

Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer

Treatment may be one of the

following:

- Surgery or other

procedures to bypass blockage in the bile duct.

- Surgery or other

procedures to bypass blockage in the bile duct followed by external-beam

radiation therapy or internal radiation therapy.

- Clinical trials

of radiation therapy with drugs to make the cancer cells more sensitive to

radiation (radiosensitizers).

- Clinical trials

of chemotherapy or biological therapy.

Recurrent

Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer

Treatment depends on many

factors, including where the cancer came back and what treatment the patient

received before. Clinical trials are testing new treatments.

BACK

|

|

Gastrointestinal Cancer

Gastrointestinal carcinoid

tumours are cancers in which malignant cells are found in certain hormone-making

cells of the digestive, or gastrointestinal, system. The digestive system

absorbs vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and water from the

food that is eaten and stores waste until the body eliminates it. The digestive

system is made up of the stomach and the small and large intestines. The last 6

feet of intestine is called the colon. The last 10 inches of the colon is the

rectum. The appendix is an organ attached to the large intestine.

There are often no signs of a

gastrointestinal carcinoid tumour in its early stages. Often the cancer will

make too much of some of the hormones, which can cause symptoms. A doctor should

be seen if the following symptoms persist:

- Pain in the

abdomen.

- Flushing and

swelling of the skin of the face and neck.

- Wheezing.

- Diarrhoea.

- Symptoms of

heart failure, including breathlessness.

If there are symptoms, a doctor

may order blood and urine tests to look for signs of cancer. Other tests may

also be done. If there is a carcinoid tumour, the patient has a greater chance

of getting other cancers in the digestive system, either at the same time or at

a later time.

The chance of recovery

(prognosis) and choice of treatment depend on whether the cancer is just in the

gastrointestinal system or has spread to other places, and on the patient's

general state of health.

There are treatments for all

patients with gastrointestinal carcinoid tumours. Four kinds of treatment are

used:

- Surgery (taking

out the cancer).

- Radiation

therapy (using high-dose x-rays to kill cancer cells).

- Biological

therapy (using the body's natural immune system to fight cancer).

- Chemotherapy

(using drugs to kill cancer cells).

Depending on where the cancer

started, the doctor may take out the cancer using one of the following

operations:

- A simple

appendectomy removes the appendix. If part of the colon is also taken out, the

operation is called a hemicolectomy. The doctor may also remove lymph nodes

and look at them under a microscope to see if they contain cancer.

- Local excision

uses a special instrument inserted into the colon or rectum through the anus

to cut the tumour out. This operation can be used for very small tumours.

- Fulguration uses

a special tool inserted into the colon or rectum through the anus. An electric

current is then used to burn the tumour away.

- Bowel resection

takes out the cancer and a small amount of healthy tissue on either side. The

healthy parts of the bowel are then sewn together. The doctor will also remove

lymph nodes and have them looked at under a microscope to see if they contain

cancer.

- Cryosurgery

kills the cancer by freezing it.

- Hepatic artery

ligation cuts and ties off the main blood vessel that brings blood into the

liver (the hepatic artery).

- Hepatic artery

embolization uses drugs or other agents to reduce or block the flow of blood

to the liver in order to kill cancer cells growing in the liver.

Radiation therapy uses

high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumours. Radiation may come

from a machine outside the body (external radiation therapy) or from putting

materials that produce radiation (radioisotopes) through thin plastic tubes in

the area where the cancer cells are found (internal radiation therapy).

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill

cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be taken by pill, or it may be put into the body

by a needle in the vein or muscle. Chemotherapy is called a systemic treatment

because the drug enters the bloodstream, travels through the body, and can kill

cancer cells outside the digestive system.

Biological therapy tries to get

the patient's body to fight the cancer. It uses materials made by the body or

made in a laboratory to boost, direct, or restore the body's natural defences

against disease. Biological therapy is sometimes called biological response

modifier (BRM) therapy or immunotherapy.

Treatment by type

Treatment of gastrointestinal

carcinoid tumour depends on the type of tumour, the stage, and the patient's

overall health.

Standard treatment may be

considered because of its effectiveness in patients in past studies, or

participation in a clinical trial may be considered. Not all patients are cured

with standard therapy and some standard treatments may have more side effects

than are desired. For these reasons, clinical trials are designed to find better

ways to treat cancer patients and are based on the most up-to-date information.

Localized

Gastrointestinal Carcinoid tumours

If the cancer started in the

appendix, the treatment will probably be surgery to remove the appendix

(appendectomy) with or without removal of part of the colon (hemicolectomy) and

lymph nodes.

If the cancer started in the

rectum, treatment will probably be simple surgery to remove the cancer, surgery

using electric current to burn the cancer away, surgery to remove part of the

rectum, or surgery to remove the anus and part of the rectum. An opening will be

made for waste to pass out of the body (colostomy) into a disposable bag

attached near the colostomy (colostomy bag).

If the cancer started in the

small intestine, the treatment will probably be surgery to remove part of the

bowel (bowel resection). Lymph nodes may also be taken out and looked at under

the microscope to see if they contain cancer.

If the cancer started in the

stomach, pancreas, or colon, the treatment will probably be surgery to remove

the organ affected by the cancer and possibly other nearby organs.

Regional

Gastrointestinal Carcinoid tumours

The treatment will probably be

surgery to remove the organ affected by the cancer and possibly other nearby

organs.

Metastatic

Gastrointestinal Carcinoid tumours

Treatment may be one of the

following:

- Surgery to

relieve symptoms caused by the cancer. Surgery to freeze and kill the cancer

may also be performed.

- Chemotherapy to

relieve symptoms caused by the cancer.

- Chemotherapy

injected directly into the hepatic artery to block the artery and kill cancer

cells growing in the liver.

- Radiation

therapy to relieve symptoms caused by the cancer.

- Radioactive

substances injected into the cancer to relieve the symptoms caused by the

cancer.

- Biological or

immunological therapy.

Carcinoid syndrome

Treatment options for

metastatic carcinoid tumour may be one of the following:

- Surgery to

remove the cancer.

- Surgery to cut

and tie the main artery that goes to the liver (hepatic artery ligation) or

injecting chemotherapy into the liver through the hepatic artery to block the

artery and kill cancer cells growing in the liver.

- Drugs designed

to relieve symptoms caused by the cancer.

- Biological

therapy to relieve symptoms caused by the cancer.

- A clinical trial

of new combinations of chemotherapy drugs.

BACK

|

|

Colon

Cancer

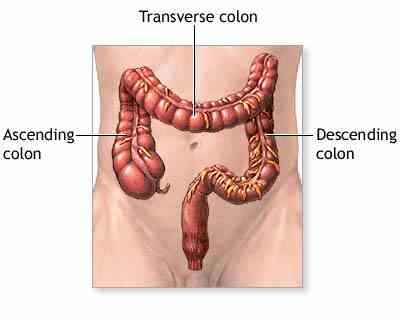

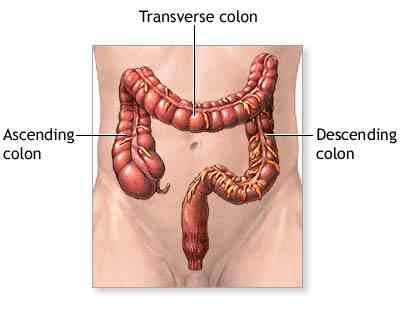

The colon is part of a section

of the digestive tract called the large intestine. The large intestine is a tube

that is 5 to 6 feet in length. The first 5 feet make up the colon, which

connects to about 6 inches of rectum, and ends with the anus. By the time food

reaches the colon (about 3 to 8 hours after eating), the nutrients have been

absorbed and it has become a liquid waste product. The colon's function is to

change this liquid waste into stool. The stool can spend anywhere from 10 hours

to several days in the colon. It has been suggested that the longer stool

remains in the colon, the higher the risk for colon cancer, but this has not

been proven.

What is colon cancer?

Colon cancer is malignant

tissue that grows in the wall of the colon. The majority of tumours begin when

normal tissue in the colon wall forms an adenomatous polyp, or pre-cancerous

growth projecting from the colon wall. As this polyp grows larger, the tumour is

formed. This process can take many years, which allows time for early detection

with screening tests.

Some tumours and polyps may

bleed intermittently, and this blood can be detected in stool samples by a test

called faecal occult blood testing (FOBT). By itself, FOBT only finds about 24%

of cancers. The sigmoidoscope is a slender, flexible tube that has the ability to view about ᄑ

of the colon. If a polyp or tumour is detected with this test, the patient must

be referred for a full colonoscopy.

The colonoscope is

similar to the sigmoidoscope, but is longer, and can view the entire colon. If a

polyp is found, the physician can remove it, and send it to a pathology lab to

determine if it is adenomatous (cancerous). As a screening method, the American

Cancer Society recommends that a colonoscopy be done every 10 years after age

50. Patients with a family or personal history should have more frequent

screenings, beginning at an earlier age than their relative was diagnosed.

Patients with a history of ulcerative colitis are also at increased risk and

should have more frequent screening than the general public. Patients should

talk with their doctor about which screening method is best for them, and how

often it should be performed.

What are the Signs of Colon

Cancer?

Unfortunately, the early stages

of colon cancer may not have any symptoms. This is why it is important to have

screening tests done even though you feel well. As the polyp grows into a

tumour, it may bleed or obstruct the colon, causing symptoms. These symptoms

include:

- Bleeding from the rectum

- Blood in the stool or toilet

after a bowel movement

- A change in the shape of the

stool (i.e. thinning)

- Cramping pain in the abdomen

- Feeling the need to have a

bowel movement when you don't have to have one

As you can see, these symptoms

can also be caused by other conditions. If you experience these symptoms, you

should be checked by a doctor.

How is Colon Cancer Diagnosed

and Staged?

After a cancer has been found,

the stage must be determined to decide on appropriate treatment. The stage tells

how far the tumour has invaded the colon wall, and if it has spread to other

parts of the body.

- Stage 0 (also called

carcinoma in situ) - the cancer is confined to the outermost portion of the

colon wall.

- Stage I - the cancer has

spread to the second and third layer of the colon wall, but not to the outer

colon wall or beyond. This is also called Dukes' A colon cancer.

- Stage II - the cancer has

spread through the colon wall, but has not invaded any lymph nodes (these are

small structures that help in fighting infection and disease). This is also

called Dukes' B colon cancer.

- Stage III - the cancer has

spread through the colon wall and into lymph nodes, but has not spread to

other areas of the body. This is also called Dukes' C colon cancer.

- Stage IV - the cancer has

spread to other areas of the body (i.e. liver and lungs). This is also called

Dukes' D colon cancer.

After the tumour and lymph

nodes are removed by a surgeon, they are examined by a pathologist, who

determines how much of the colon wall and lymph nodes have been invaded by

tumour. Patients with invasive cancer (stages II, III, and IV) require a staging

workup, including full colonoscopy, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level (a

marker for colon cancer found in the blood), chest x-ray, and CT scan of the

abdomen and pelvis, to determine if the cancer has spread.

What are the Treatments for

Colon Cancer?

Surgery Surgery

Surgery is the most common

treatment for colon cancer. If the cancer is limited to a polyp, the patient can

undergo a polypectomy (removal of the polyp), or a local excision, where a small

amount of surrounding tissue is also removed. If the tumour invades the bowel

wall or surrounding tissues, the patient will require a partial resection

(removal of the cancer and a portion of the bowel) and removal of local lymph

nodes to determine if the cancer has spread into them. After the tumour is

removed, the two ends of the remaining colon are reconnected, allowing normal

bowel function. In some situations, it may not be possible to reconnect the

colon, and a colostomy (an opening in the abdominal wall to allow passage of

stool) is needed.

Chemotherapy

Despite the fact that a

majority of patients have the entire tumour removed by surgery, as many as 40%

will develop a recurrence. Chemotherapy is given to reduce this chance of

recurrence. There is some controversy over patients with stage II disease

receiving chemotherapy. Studies have not consistently shown a benefit in

treating these patients. Generally, patients with stage II disease who present

with a bowel perforation or obstruction, or have poorly differentiated tumours

(determined by a pathologist), are considered at higher risk for recurrence, and

are treated with 6 to 8 months of Fluorouracil (5-FU) and Leucovorin (LV) (both

chemotherapy agents). Other patients with stage II disease are followed closely,

but generally receive no chemotherapy. Patients who present with stage III colon

cancer are typically treated with a regimen of

Fluorouracil and Leucovorin for 12 months.

Forty to fifty percent of

patients have metastatic (disease that has spread to other organs) at the time

of diagnosis, or have a recurrence of the disease after therapy. Unfortunately,

the prognosis for these patients is poor. The standard therapy for patients with

advanced disease is

Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and

irinotecan (CPT-11). This regimen was found to be more

effective than Fluorouracil and Leucovorin alone in these patients. With this

therapy, an average of 39% of patients have a response, but the average survival

is still only 15 months. Patients and their physicians must weigh the benefits

of therapy versus the side effects of the treatment. Younger patients and those

in better physical shape are better able to tolerate therapy.

Two new medications,

capecitabine (Xeloda) and oxaliplatin, are also being used in the treatment of

advanced colon cancer. Capecitabine is currently approved by the FDA for the

treatment of advanced colon cancer that has failed treatment, but is still being

investigated in untreated patients. Oxaliplatin is widely used in Europe, but

has not yet been approved by the FDA for use in the United States. Currently,

patients can only receive this medication in a clinical trial.

Radiotherapy

Colon cancer is not typically

treated with radiation therapy. If the cancer has invaded another organ, or

adhered to the abdominal wall, radiation therapy may be one option. One way to

understand this is that radiation needs a "target". If the tumour has been

surgically resected, there is no target to radiate. If the tumour has spread to

other organs, chemotherapy is needed to reach all the tumour cells, whereas

radiation can only treat a small area.

BACK

|

|

Oesophageal

Cancer Oesophageal cancer is a disease in which

malignant cells form in the tissues of the oesophagus.

The oesophagus is the hollow, muscular tube that moves food and liquid from the

throat to the stomach. The wall of the oesophagus is made up of several layers

of tissue, including mucous membrane, muscle, and connective tissue. Oesophageal

cancer starts at the inside lining of the oesophagus and spreads outward through

the other layers as it grows. The two most common forms of oesophageal cancer are named for the type of cells

that become malignant (cancerous):

The two most common forms of oesophageal cancer are named for the type of cells

that become malignant (cancerous):

- Squamous cell carcinoma: Cancer that forms in squamous cells, the thin, flat

cells lining the oesophagus. This cancer is most often found in the upper and

middle part of the oesophagus, but can occur anywhere along the oesophagus. This

is also called epidermoid carcinoma.

- Adenocarcinoma: Cancer that begins in glandular (secretory) cells. Glandular

cells in the lining of the oesophagus produce and release fluids such as mucus.

Adenocarcinomas usually form in the lower part of the oesophagus, near the

stomach.

Smoking, heavy alcohol use, and Barrettís oesophagus can affect the risk of

developing oesophageal cancer.

Risk factors include the following:

- Tobacco use

- Heavy alcohol use

- Barrettís oesophagus: A condition in which the cells lining the lower part of

the oesophagus have changed or been replaced with abnormal cells that could lead

to cancer of the oesophagus. Gastric reflux (the backing up of stomach contents

into the lower section of the oesophagus) may irritate the oesophagus and, over

time, cause Barrettís oesophagus

- Older age

- Being male

- Being African-American

The most common signs of oesophageal cancer

are painful or difficult swallowing and weight loss.

These and other symptoms may be caused by oesophageal cancer or by other

conditions. A doctor should be consulted if any of the following problems occur

-

Painful or

difficult swallowing

-

Weight loss

-

Pain behind

the breastbone

-

Hoarseness

and cough

-

Indigestion and heartburn

Tests that examine the oesophagus are used to detect (find) and diagnose

oesophageal cancer. The following tests and procedures may be used:

Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a

type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture

of areas inside the body.

Barium swallow: A series of x-rays of the oesophagus and stomach. The patient

drinks a l iquid

that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound). The liquid coats the

oesophagus and x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called an upper GI

series. iquid

that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound). The liquid coats the

oesophagus and x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called an upper GI

series.

Oesophagoscopy: A procedure to look inside the oesophagus to check for abnormal

areas. An oesophagoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted through the mouth

and down the throat into the oesophagus. Tissue samples may be taken for biopsy.

Biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope

to check for signs of cancer. The biopsy is usually done during an

oesophagoscopy. Sometimes a biopsy shows changes in the oesophagus that are not

cancer but may lead to cancer.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options depend on the

following:

- The stage of the cancer

(whether it affects part of the oesophagus, involves the whole

oesophagus, or has spread to other places in the body)

- The size of the tumour

- The patientís general

health

- When oesophageal cancer is found very early, there is a better chance of

recovery. Oesophageal cancer is often in an advanced stage when it is diagnosed.

At later stages, oesophageal cancer can be treated but rarely can be cured.

Taking part in one of the clinical trials being done to improve treatment should

be considered.

Stages

of Oesophageal Cancer Stages

of Oesophageal Cancer

After oesophageal cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if

cancer cells have spread within the oesophagus or to other parts of the body.

The following stages are used for oesophageal cancer:

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

Stage I

Stage II

Stage III

Stage IV

After oesophageal cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if

cancer cells have spread within the oesophagus or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer cells have spread within the oesophagus

or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from

the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know

the stage in order to plan treatment. The following tests and procedures may be

used in the staging process:

Bronchoscopy: A procedure to look inside the trachea and large airways in

the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted

through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. Tissue samples may be

taken for biopsy.

Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a

type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture

of areas inside the body.

Laryngoscopy: A procedure in which the doctor examines the larynx (voice

box) with a mirror or with a laryngoscope (a thin, lighted tube).

CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of

areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a

computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or

swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This test is also

called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial

tomography.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): A procedure in which an endoscope (a thin,

lighted tube) is inserted into the body. The endoscope is used to bounce

high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off internal tissues or organs and make

echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. This

procedure is also called endosonography.

Thoracoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the chest

to check for abnormal areas. An incision (cut) is made between two ribs and a

thoracoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted into the chest. Tissue samples

and lymph nodes may be removed for biopsy. In some cases, this procedure may be

used to remove portions of the oesophagus or lung.

Laparoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the

abdomen to check for abnormal areas. An incision (cut) is made in the abdominal

wall and a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted into the abdomen.

Tissue samples and lymph nodes may be removed for biopsy.

PET scan (positron emission tomography scan): A procedure to find

malignant tumour cells in the body. A small amount of radionuclide glucose

(sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and

makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumour

cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up

more glucose than normal cells. The use of PET for staging oesophageal cancer is

being studied in clinical trials.

The following stages are used for oesophageal cancer:

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

In stage 0, cancer is found only in the innermost layer of cells lining the

oesophagus. Stage 0 is also called carcinoma in situ.

Stage I

In stage I, cancer has spread beyond the innermost layer of cells to the next

layer of tissue in the wall of the oesophagus.

Stage II

Stage II oesophageal cancer is divided into stage IIA and stage IIB, depending

on where the cancer has spread.

Stage IIA: Cancer has spread to the layer of oesophageal muscle or to the

outer wall of the oesophagus.

Stage IIB: Cancer may have spread to any of the first three layers of the

oesophagus and to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage III

In stage III, cancer has spread to the outer wall of the oesophagus and may have

spread to tissues or lymph nodes near the oesophagus.

Stage IV

Stage IV oesophageal cancer is divided into stage IVA and stage IVB, depending

on where the cancer has spread.

Stage IVA: Cancer has spread to nearby or distant lymph nodes.

Stage IVB: Cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes and/or organs in other parts

of the body.

Recurrent Oesophageal Cancer

Recurrent oesophageal cancer is cancer that has recurred after it has been

treated. The cancer may come back in the oesophagus or in other parts of the

body.

There are different types of treatment for patients with oesophageal cancer.

Different types of treatment are available for patients with oesophageal cancer.

Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being

tested in clinical trials. Before starting treatment, patients may want to think

about taking part in a clinical trial. A treatment clinical trial is a research

study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new

treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new

treatment is better than the ďstandardĒ treatment, the new treatment may become

the standard treatment.

Five types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery is the most common treatment for cancer of the oesophagus. Part of the

oesophagus may be removed in an operation called an oesophagectomy. The doctor

will connect the remaining healthy part of the oesophagus to the stomach so the

patient can still swallow. A plastic tube or part of the intestine may be used

to make the connection. Lymph nodes near the oesophagus may also be removed and

viewed under a microscope to see if they contain cancer. If the oesophagus is

partly blocked by the tumour, an expandable metal stent (tube) may be placed

inside the oesophagus to help keep it open.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other

types of radiation to kill cancer cells. There are two types of radiation

therapy. External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send

radiation toward the cancer. Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive

substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly

into or near the cancer. The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the

type and stage of the cancer being treated.

A plastic tube may be inserted into the oesophagus to keep it open during

radiation therapy. This is called intraluminal intubation and dilation.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer

cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping the cells from dividing. When

chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs

enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic

chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly in the spinal column, a body

cavity such as the abdomen, or an organ, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in

those areas. The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type and stage of

the cancer being treated.

Laser therapy

Laser therapy is a cancer treatment that uses a laser beam (a narrow beam of

intense light) to kill cancer cells.

Electrocoagulation

Electrocoagulation is the use of an electric current to kill cancer cells.

Patients have special nutritional needs during treatment for oesophageal cancer.

Many people with oesophageal cancer find it hard to eat because they have

difficulty swallowing. The oesophagus may be narrowed by the tumour or as a side

effect of treatment. Some patients may receive nutrients directly into a vein.

Others may need a feeding tube (a flexible plastic tube that is passed through

the nose or mouth into the stomach) until they are able to eat on their own.

Treatment Options By Stage

Stage 0 Oesophageal Cancer (Carcinoma in Situ)

Treatment of stage 0 oesophageal cancer (carcinoma in situ) is usually surgery.

Stage I Oesophageal Cancer

Treatment of stage I oesophageal cancer may include the following:

Surgery.

Clinical trials of chemotherapy plus radiation therapy, with or without surgery.

Clinical trials of new therapies used before or after surgery.

Stage II Oesophageal Cancer

Treatment of stage II oesophageal cancer may include the following:

Surgery.

Clinical trials of chemotherapy plus radiation therapy, with or without surgery.

Clinical trials of new therapies used before or after surgery.

Stage III Oesophageal Cancer

Treatment of stage III oesophageal cancer may include the following:

Surgery.

Clinical trials of chemotherapy plus radiation therapy, with or without surgery.

Clinical trials of new therapies used before or after surgery.

Stage IV Oesophageal Cancer

Treatment of stage IV oesophageal cancer may include the following:

External or internal radiation therapy as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms

and improve quality of life.

Laser surgery or electrocoagulation as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms

and improve quality of life.

Chemotherapy.

Clinical trials of chemotherapy.

Treatment Options for Recurrent Oesophageal Cancer

Treatment of recurrent oesophageal cancer may include the following:

Use of any standard treatments as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and

improve quality of life.

Clinical trials of new therapies used before or after surgery.

BACK

|

|

Gallbladder

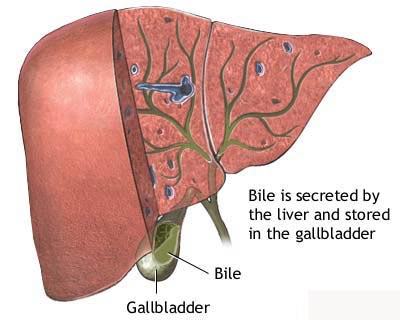

Cancer Cancer of the gallbladder, an

uncommon cancer, is a disease in which cancer cells are found in the tissues of

the gallbladder. The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ that lies just under the liver in the upper abdomen. Bile, a fluid made by the liver, is stored

in the gallbladder. When food is being broken down (digested) in the stomach and

the intestines, bile is released from the gallbladder through a tube called the

bile duct that connects the gallbladder and liver to the first part of the small

intestine. The bile helps to digest fat.

under the liver in the upper abdomen. Bile, a fluid made by the liver, is stored

in the gallbladder. When food is being broken down (digested) in the stomach and

the intestines, bile is released from the gallbladder through a tube called the

bile duct that connects the gallbladder and liver to the first part of the small

intestine. The bile helps to digest fat.

Cancer of the gallbladder is

more common in women than in men. It is also more common in people who have hard

clusters of material in their gallbladder (gallstones).

Cancer of the gallbladder is

hard to find (diagnose) because the gallbladder is hidden behind other organs in

the abdomen. Cancer of the gallbladder is sometimes found after the gallbladder

is removed for other reasons. The symptoms of cancer of the gallbladder may be

like other diseases of the gallbladder, such as gallstones or infection, and

there may be no symptoms in the early stages. A doctor should be seen if the

following symptoms persist: Cancer of the gallbladder is

hard to find (diagnose) because the gallbladder is hidden behind other organs in

the abdomen. Cancer of the gallbladder is sometimes found after the gallbladder

is removed for other reasons. The symptoms of cancer of the gallbladder may be

like other diseases of the gallbladder, such as gallstones or infection, and

there may be no symptoms in the early stages. A doctor should be seen if the

following symptoms persist:

- Pain above the

stomach

- Loss of weight

without trying

- Fever

- Yellowing of the

skin (jaundice)

If there are symptoms, a doctor

may order x-rays and other tests to see what is wrong. However, usually the

cancer cannot be found unless the patient has surgery. During surgery, a cut is

made in the abdomen so that the gallbladder and other nearby organs and tissues

can be examined.

The chance of recovery and

choice of treatment depend on the stage of cancer (whether it is just in the

gallbladder or has spread to other places) and on the patientís general health.

Stage Explanation

Stages of cancer of the

gallbladder

Once cancer of the gallbladder

is found, more tests will be done to find out if cancer cells have spread to

other parts of the body. A doctor needs to know the stage to plan treatment. The

following stages are used for cancer of the gallbladder:

Localized

Cancer is found only in the

tissues that make up the wall of the gallbladder, and it can be removed

completely in an operation.

Unresectable

All of the cancer cannot be

removed in an operation. Cancer has spread to the tissues around the

gallbladder, such as the liver, stomach, pancreas, or intestine and/or to lymph

nodes in the area. (Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped structures that are found

throughout the body. They produce and store infection-fighting cells.)

Recurrent

Recurrent disease means that

the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has been treated. It may come back

in the gallbladder or in another part of the body.

How cancer of the

gallbladder is treated

There are treatments for all

patients with cancer of the gallbladder. Three treatments are used:

- Surgery (taking

out the cancer or relieving symptoms of the cancer in an operation)

- Radiation

therapy (using high-dose x-rays to kill cancer cells)

- Chemotherapy

(using drugs to kill cancer)

Surgery is a common treatment

of cancer of the gallbladder if it has not spread to surrounding tissues. The

doctor may take out the gallbladder in an operation called a cholecystectomy.

Part of the liver around the gallbladder and lymph nodes in the abdomen may also

be removed.

If the cancer has spread and

cannot be removed, the doctor may do surgery to relieve symptoms. If the cancer