Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the

tissues of the cervix. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the major risk

factor for development of cervical cancer. There are usually no noticeable signs

of early cervical cancer but it can be detected early with yearly check-ups.

Possible signs of cervical cancer include vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain.

Tests that examine the cervix are used to detect and diagnose cervical cancer.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery)

and treatment options.

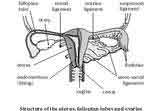

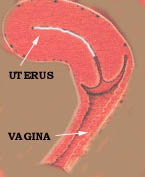

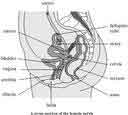

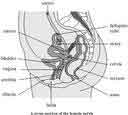

Cervical cancer is a disease in which malignant cells form in the tissues of

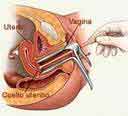

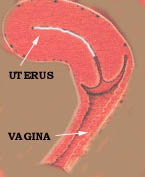

the cervix. The cervix is the lower, narrow end of the uterus (the hollow,

pear-shaped organ where a foetus grows). The cervix leads from the uterus to the

vagina (birth canal). Cervical cancer usually develops slowly over time. Before

cancer appears in the cervix, the cells of the cervix go through changes known

as dysplasia, in which cells that are not normal begin to appear in the cervical

tissue. Later, cancer cells start to grow and spread more deeply into the cervix

and to surrounding areas.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the major risk factor

for development of cervical cancer. Infection of the cervix with human

papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common cause of cervical cancer. Not all women

with HPV infection, however, will develop cervical cancer. Women who do not

regularly have a Pap smear to detect HPV or abnormal cells in the cervix are at

increased risk of cervical cancer.

Other possible risk factors include the following:

-

Giving

birth to many children

-

Having many

sexual partners

-

Having

first sexual intercourse at a young age

-

Smoking

cigarettes

-

A diet

lacking in vitamins A and C

-

Oral

contraceptive use ("the Pill")

-

Weakened immune system

There are usually no noticeable signs of early cervical cancer

but it can be detected early with yearly check-ups. Early cervical cancer may

not cause noticeable signs or symptoms. Women should have yearly check-ups,

including a Pap smear to check for abnormal cells in the cervix. The prognosis

(chance of recovery) is better when the cancer is found early. Possible signs of

cervical cancer include vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain. These and other

symptoms may be caused by cervical cancer or

by other conditions. A doctor should be consulted if any of the following

problems occur:

Vaginal bleeding. Vaginal bleeding.

Unusual vaginal discharge.

Pelvic pain.

Pain during sexual intercourse.

Tests that examine the cervix are used to detect and diagnose

cervical cancer. The following procedures may be used:

-

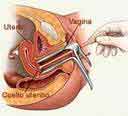

Pap smear: A procedure to collect cells from the surface of

the cervix and vagina. A piece of cotton, a brush, or a

small wooden stick is used to gently scrape cells from the

cervix and vagina. The cells are viewed under a microscope

to find out if they are abnormal. This procedure is also

called a Pap test.

-

Colposcopy: A procedure to look inside the vagina and cervix

for abnormal areas. A colposcope (a thin, lighted tube) is

inserted through the vagina into the cervix. Tissue samples

may be taken for biopsy.

-

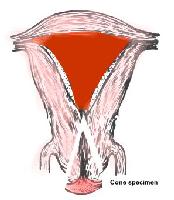

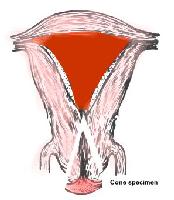

Biopsy: If abnormal cells are found in a Pap smear, the

doctor may do a biopsy. A sample of tissue is cut from the

cervix and viewed under a microscope. A biopsy that removes

only a small amount of tissue is usually done in the

doctor’s office. A woman may need to go to a hospital for a

cervical cone biopsy (removal of a larger, cone-shaped

sample of cervical tissue).

-

Pelvic exam: An exam of the vagina, cervix, uterus,

fallopian tubes, ovaries, and rectum. The doctor or nurse

inserts one or two lubricated, gloved fingers of one hand

into the vagina and the other hand is placed over the lower

abdomen to feel the size, shape, and position of the uterus

and ovaries. A speculum is also inserted into the vagina and

the doctor or nurse looks at the vagina and cervix for signs

of disease. A Pap test or Pap smear of the cervix is usually

done. The doctor or nurse also inserts a lubricated, gloved

finger into the rectum to feel for lumps or abnormal areas.

-

Endocervical curettage: A procedure to collect cells or

tissue from the cervical canal using a curette (spoon-shaped

instrument). Tissue samples may be taken for biopsy. This

procedure is sometimes done at the same time as a

colposcopy.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options. The prognosis depends on the following:

-

The stage of the cancer (whether it

affects part of the cervix, involves the whole cervix, or has spread to the

lymph nodes or other places in the body)

-

The type of

cervical cancer

-

The size of

the tumour

Treatment options depend on the following:

Treatment of cervical cancer during pregnancy depends on the stage of the cancer

and the stage of the pregnancy. For cervical cancer found early or for cancer

found during the last trimester of pregnancy, treatment may be delayed until

after the baby is born.

Stages of Cervical Cancer

After cervical cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer

cells have spread within

the cervix or to other parts of the body. The following stages are used for

cervical cancer:

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

Stage I

Stage II

Stage III

Stage IV

After cervical cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer

cells have spread within the cervix or to other parts of the body. The process

used to find out if cancer has spread within the

cervix or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered

from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to

know the stage in order to plan treatment. The following tests and procedures

may be used in the staging process:

-

Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the

chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through

the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the

body.

-

CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of

detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from

different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked

to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or

swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more

clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography,

computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

-

Lymphangiogram: A procedure used to x-ray the lymph system.

A dye is injected into the lymph vessels in the feet. The

dye travels upward through the lymph nodes and lymph

vessels, and x-rays are taken to see if there are any

blockages. This test helps find out whether cancer has

spread to the lymph nodes.

-

Pre-treatment surgical staging: Surgery (an operation) is

done to find out if the cancer has spread within the cervix

or to other parts of the body. In some cases, the cervical

cancer can be removed at the same time. Pre-treatment

surgical staging is usually done only as part of a clinical

trial.

-

Ultrasound: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves

(ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and

make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues

called a sonogram.

-

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a

magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of

detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure

is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

The results of these tests are viewed together with the results

of the original tumour biopsy to determine the cervical cancer stage.

The following stages are used for cervical cancer:

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

In stage 0, cancer is found in the first layer of cells lining the cervix only

and has not invaded the deeper tissues of the cervix. Stage 0 is also called

carcinoma in situ.

Stage I:In stage I, cancer is found in the cervix only. Stage I

is divided into stages IA and IB, based on the amount of cancer that is found.

Stage IA: A very small amount of cancer that can only be seen

with a microscope is found in the tissues of the cervix. The cancer is not

deeper than 5 millimetres (less than ¼ inch) and not wider than 7 millimetres

(about ¼ inch).

Stage IB: In stage IB, cancer is still within the cervix and

either can only be seen with a microscope and is deeper than 5 millimetre (less

than ¼ inch) or wider than 7 millimetres (about ¼ inch) or can be seen without a

microscope and may be larger than 4 centimetres (about 1 ½ inches).

Stage II: In stage II, cancer has spread beyond the cervix but

not to the pelvic wall (the tissues that line the part of the body between the

hips). Stage II is divided into stages IIA and IIB, based on how far the cancer

has spread.

Stage IIA: Cancer has spread beyond the cervix to the upper two

thirds of the vagina but not to tissues around the uterus.

Stage IIB: Cancer has spread beyond the cervix to the upper two thirds of the

vagina and to the tissues around the uterus.

Stage III: In stage III, cancer has spread to the lower third of the vagina and

may have spread to the pelvic wall and nearby lymph nodes. Stage III is divided

into stages IIIA and IIIB, based on how far the cancer has spread.

Stage IIIA: Cancer has spread to the lower third of the vagina

but not to the pelvic wall.

Stage IIIB: Cancer has spread to the pelvic wall and/or the

tumour has become large enough to block the ureters (the tubes that connect the

kidneys to the bladder). This blockage can cause the kidneys to enlarge or stop

working. Cancer cells may also have spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis.

Stage IV: In stage IV, cancer has spread to the bladder, rectum or other parts

of the body. Stage IV is divided into stages IVA and IVB, based on where the

cancer is found.

Stage IVA: Cancer has spread to the bladder or rectal wall and may have spread

to lymph nodes in the pelvis.

Stage IVB: Cancer has spread beyond the pelvis and pelvic lymph nodes to other

places in the body, such as the abdomen, liver, intestinal tract, or lungs.

There are different types of treatment for patients with cervical cancer. Three

types of standard treatment are used:

There are different types of treatment for patients with cervical cancer.

Different types of treatment are available for patients with cervical cancer.

Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being

tested in clinical trials. Before starting treatment, patients may want to think

about taking part in a clinical trial. A treatment clinical trial is a research

study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new

treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new

treatment is better than the “standard” treatment, the new treatment may become

the standard treatment. Three types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery (removing the cancer in an operation) is sometimes used

to treat cervical cancer. The following surgical procedures may be used:

-

Conization: A procedure to remove a cone-shaped piece of

tissue from the cervix and cervical canal. A pathologist views the tissue

under a microscope to look for cancer cells. Conization may be used to

diagnose or treat a cervical condition. This procedure is also called a cone

biopsy.

-

Hysterectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the uterus and

cervix. If the uterus and cervix are taken out through the vagina, the

operation is called a vaginal hysterectomy. If the uterus and cervix are taken

out through a large incision in the abdomen, the operation is called a total

abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterus and cervix are taken out through a small

incision in the abdomen using a laparoscope, the operation is called a total

laparoscopic hysterectomy.

-

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: A surgical procedure to

remove both ovaries and both fallopian tubes.

-

Radical hysterectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the

uterus, cervix, and part of the vagina. The ovaries or lymph nodes may also be

removed.

-

Pelvic exenteration: A surgical procedure to remove the lower

colon, rectum, and bladder. In women, the cervix, vagina, ovaries, and nearby

lymph nodes are also removed. Artificial openings (stoma) are made for urine

and stool to flow from the body to a collection bag. Plastic surgery may be

needed to make an artificial vagina after this operation.

-

Cryosurgery: A treatment that uses an instrument to freeze and

destroy abnormal tissue, such as carcinoma in situ. This type of treatment is

also called cryotherapy. Laser surgery: A cancer treatment that uses a laser beam (a

narrow beam of intense light) as a knife to remove cancer. Loop

electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP): A treatment that uses electrical

current passed through a thin wire loop as a knife to remove abnormal tissue

or cancer.

-

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy

x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells. There are two types

of radiation therapy. External radiation therapy

uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Internal

radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds,

wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. The way

the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of

the cancer being treated.

-

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the

growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping the cells

from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or

muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout

the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly

into the spinal column, a body cavity such as the abdomen, or an organ, the

drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas. The way the chemotherapy is

given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

Other types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

BACK

|

|

Endometrial cancer originates in the endometrial lining of the uterus. It is the

most common gynaecological malignancy (cancer originating in female reproductive

organs). The disease normally occurs in postmenopausal women, the average

age at diagnosis being about 60 years.

Endometrial cancer is considered an oestrogen-dependent

disease. Oestrogen is a hormone that is secreted by the ovaries. It plays an

important role in the development of the female reproductive system and is

largely responsible for the physiologic changes that occur during menstruation,

puberty, and pregnancy. Progesterone is another hormone secreted by the ovaries

that plays an important role. Normally, both oestrogen and progesterone are

secreted in certain proportions. Chronic exposure to oestrogen, without the

accompanying balancing effects of progesterone, is considered the major risk

factor for endometrial cancer and may play a causal role in the development of

the disease. Endometrial cancer is considered an oestrogen-dependent

disease. Oestrogen is a hormone that is secreted by the ovaries. It plays an

important role in the development of the female reproductive system and is

largely responsible for the physiologic changes that occur during menstruation,

puberty, and pregnancy. Progesterone is another hormone secreted by the ovaries

that plays an important role. Normally, both oestrogen and progesterone are

secreted in certain proportions. Chronic exposure to oestrogen, without the

accompanying balancing effects of progesterone, is considered the major risk

factor for endometrial cancer and may play a causal role in the development of

the disease.

Benign uterine tumours, known as fibroids, usually are

asymptomatic and do not require treatment. If fibroids cause bleeding or pain,

they may be surgically removed. Cancerous (malignant) uterine tumours spread to

other tissues and organs if left untreated. Endometrial cancer refers

specifically to tumours that originate in the endometrial lining of the uterus.

If the tumour originates in the deeper, muscular walls of the uterus, it is

called uterine sarcoma. About 90% of all uterine cancers are endometrial.

A precancerous condition called endometrial hyperplasia, or

adenomatous hyperplasiam, may cause irregular uterine bleeding. This condition

can be mild, moderate, or severe. Severe hyperplasia is considered carcinoma in

situ, the earliest detectable stage of endometrial cancer.

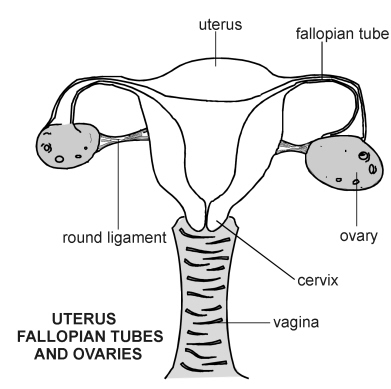

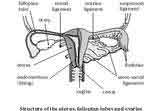

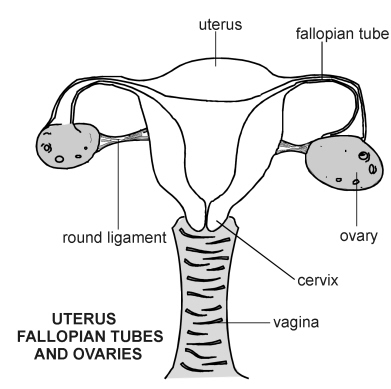

Anatomy of the uterus and endometrium

The uterus (womb) is a muscular, upside-down, pear-shaped organ that is located

in a woman's pelvis behind the bladder and in front of the rectum. The top,

wider part of the uterus is called the fundus (body), and the bottom, narrow

part is the cervix. The fundus has very thick, muscular walls that are lined

with a mucous surface called the endometrium.

Two uterine tubes, the fallopian tubes or oviducts, lead from

either side of the upper part of the uterus to the ovaries. The ovaries are

paired organs, one on each side of the pelvis. Ova (eggs) are transported from

the ovaries to the uterus via the fallopian tubes.

All of the parts of the female genital tract, from the ovaries

to the vagina, are held together by various types of connective tissue. For

example, there is a thin, delicate sheet of lining called the peritoneum that

covers the uterus and extends over the bladder and rectum, keeping the uterus

snug between the latter two organs. But, despite all the well-connected organs,

the female genital tract is more mobile and plastic than any other part of a

woman's body. The ovaries rupture monthly, the uterus sheds countless cells

during menstruation, and the changes that a woman's uterus undergo during

pregnancy are the most dramatic changes that any human organ experiences without

suffering damage. A woman's reproductive system is incredibly responsive to

hormonal changes in its environment. The endometrium is no exception. It is very

sensitive to hormonal changes, and it is believed that endometrial cancer may be

caused by an imbalance in its hormonal environment.

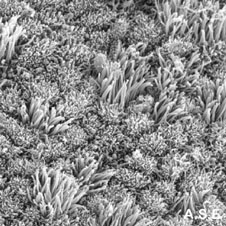

The endometrium contains several layers of cells that vary in

appearance and amount as a woman's menstrual cycle changes. It is full of

glandular cells and blood vessels. Nearly all of the cells are responsive to the

hormonal changes that the uterus regularly experiences. Certain cells undergo

what is called hyperplasia, increased cell division, in response to oestrogen.

It is this cell-growing response to oestrogen that leads many researchers to

believe that oestrogen likely plays a causal role in the development of

endometrial cancer.

The uterus has a flat, inner surface and is covered with tall,

columnar epithelial cells. There are pits in the surface that lead down into

uterine glands. The columnar cells, the pits, and the connective tissue and

blood vessels that surround the glands are all part of the endometrium. The

endometrium undergoes dramatic changes during a woman's menstrual cycle. During

the luteal phase, for example, the two-week period just before a woman bleeds,

the endometrium is thick, its epithelial cells are enlarged, the glands bulging,

and the arteries swollen. At menstruation, the arteries break, the epithelial

cells die, and the endometrium, in effect, sheds. Following menstruation, during

the follicular phase, the endometrium regenerates. The changing thickness of the

endometrium is highly dependent on the secretion of oestrogen and progesterone.

Oestrogen causes cellular growth and is an important component of the

rebuilding, follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone is secreted

during the later, thick-walled luteal phase, and it balances out the effects of

the oestrogen. Abnormal growth of endometrial cells (whether cancerous or not)

and endometrial cancer are believed to be due to chronic exposure to too much

oestrogen without the balancing effect of progesterone. The uterus has a flat, inner surface and is covered with tall,

columnar epithelial cells. There are pits in the surface that lead down into

uterine glands. The columnar cells, the pits, and the connective tissue and

blood vessels that surround the glands are all part of the endometrium. The

endometrium undergoes dramatic changes during a woman's menstrual cycle. During

the luteal phase, for example, the two-week period just before a woman bleeds,

the endometrium is thick, its epithelial cells are enlarged, the glands bulging,

and the arteries swollen. At menstruation, the arteries break, the epithelial

cells die, and the endometrium, in effect, sheds. Following menstruation, during

the follicular phase, the endometrium regenerates. The changing thickness of the

endometrium is highly dependent on the secretion of oestrogen and progesterone.

Oestrogen causes cellular growth and is an important component of the

rebuilding, follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone is secreted

during the later, thick-walled luteal phase, and it balances out the effects of

the oestrogen. Abnormal growth of endometrial cells (whether cancerous or not)

and endometrial cancer are believed to be due to chronic exposure to too much

oestrogen without the balancing effect of progesterone.

Treatment

The treatment of endometrial cancer depends on many factors, including a

patient's general health, age, and stage of the disease. In the early stages, endometrial cancer is usually treated with

surgery and/or radiation. In the later stages, it

is usually treated with hormone therapy. There are

numerous treatment options for patients.

Surgery

The typical surgery is bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, the removal of the

ovaries and fallopian tubes, as well as a complete, radical hysterectomy. A

radical hysterectomy involves removing the uterus, the tissues surrounding the

uterus, and the upper third of the vagina. A hysterectomy can be either

abdominal or vaginal. In an abdominal hysterectomy, the surgeon makes an

incision in the front of the abdomen and removes the uterus. In a vaginal

hysterectomy, the uterus is removed through the vagina. Because endometrial

cancer originates in the uterine body, a hysterectomy should be sufficient, but

the ovaries are removed as well because they are the most common sites of

undetected metastasis. Also, most women who undergo the surgery are

postmenopausal, and their ovaries are no longer providing the hormonal function

that is so important before menopause. During an abdominal hysterectomy, the

lymph nodes are also almost always sampled (a pelvic lymph node dissection) to

detect any spread of cancer to the lymph nodes.

Until recently, if a vaginal hysterectomy was used to remove the uterus,

there was no way to get a sample of lymph node tissue. Now, however, there is a

new surgical technique called laparascopic lymph node sampling that many

surgeons are beginning to use that allows for sampling the lymph nodes even when

the abdomen is not cut open for an abdominal hysterectomy. Thus women can opt

for a vaginal hysterectomy and still have their lymph nodes examined. The new

method involves inserting a tube through a very small opening in the abdomen.

The vaginal hysterectomy combined with the laparascopy are much less invasive

and require less recovery time than an abdominal hysterectomy.

Although the primary treatment for any stage endometrial cancer involves a

radical hysterectomy, according to the National Cancer Institute, early stage I

cancers may not require a radical hysterectomy. A simple hysterectomy,which

involves removal of the uterus but not the surrounding tissues or upper third of

the vagina, may be sufficient. It is important that you discuss with your

surgeon the different options and why she or he thinks one procedure is more

appropriate than another.

Radiation

There are two types of radiotherapy commonly used to treat various stages and

grades of endometrial cancer: external-beam

pelvic radiation and

intra-cavitary

irradiation.

External beam pelvic radiation

Radiotherapy was first used to treat uterine cancer around the turn of the

century, very shortly after Marie Curie's discovery of radium. For many decades,

radiation therapy was used as a standard pre-surgical treatment, but it is no

longer done preoperatively because it prevents accurate surgical staging. It is

standard to reserve the use of radiotherapy until an initial hysterectomy, at

least, has been performed. Even following a hysterectomy and bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy, however, the effectiveness of adjuvant radiation therapy

(therapy used in addition to surgery) is controversial. Although regional pelvic

radiation has proven to decrease pelvic recurrences, it does not necessarily

improve the survival rate. It is likely most beneficial for patients with

tumours that are confined to the pelvis and that have features that increase the

likelihood of recurrence (stages IC to IIIC). The potential benefits of

radiation should be weighed against the risks, such as a history of pelvic

infections or severe diabetes mellitus.

Postoperative vaginal irradiation (brachytherapy)

In addition to pelvic radiation, postoperative vaginal irradiation is often used

to prevent vaginal cuff recurrences (the vaginal cuff is the upper third of the

vagina). Vaginal cuff recurrences are common for certain types of tumours. This

type of therapy involves inserting small metal cylinders, or some other type of

applicator, through the vagina, where it releases a radioactive substance over

the course of two or three days.

Hormonal therapy

Hormones, particularly progesterone, can be used to treat metastatic endometrial

cancer, but their effectiveness is not very great. Studies indicate that less

than 20% of patients who are treated with hormones respond to the treatment.

Chemotherapy

Studies have not yet produced clear results on the effectiveness of chemotherapy

to treat endometrial cancer. Chemotherapy is potentially most useful for cancers

that have spread to distant parts of the body.

Treatment by stage

Stages I and II

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy plus radiation, depending on

the grade of the tumour and whether it has invaded the myometrium.

Stage IA, grade 1 or 2 tumour

Usually there is a low risk of disease recurrence, therefore radiation therapy

is not used. Treatment is surgery only.

Stage IA, grade 3 tumour; all stage II tumours

There is an intermediate risk for disease recurrence in these patients, although

it is not clear that postoperative radiation therapy improves survival. It does,

however, decrease the risk of local relapse. Following surgery, it is important

that patients be given the opportunity to participate in clinical, postoperative

radiation therapy trials. Either vaginal cuff radiation (internal radiation of

the upper third of the vagina) or pelvic radiation should be considered.

Stages III and IVA (all grade tumours)

Following surgery, vaginal cuff radiotherapy with or without pelvic or whole

abdominal radiation may increase a woman's chances of survival. Progesterone is

used for metastatic endometrial cancer.

Stage IVB

This group of women have distant spread of the disease at the time of diagnosis.

The chance of cure in this group is, unfortunately, low. If possible, patients

can participate in a clinical trial. If not possible, or if they choose not to

participate, palliative (pain-relieving) therapy should be considered.

Palliation of symptoms can include hormones, chemotherapy, or radiation.

Recurrent disease

Recurrence is more likely in women with advanced disease and in those whose

tumour had certain high-risk features. Usually recurrence happens within three

years of the original diagnosis. Hormone therapy can be used to treat recurrent

disease, although its effectiveness does not appear to be that great. The use of

various combinations of hormones are currently being evaluated. The use of

chemotherapy to treat recurrent disease is also currently being evaluated. If a

woman was originally treated only with surgery and no radiation, if the cancer

recurs, either external-beam pelvic or intracavitary radiation can be used as

therapy. In the case of radiation, the prognosis depends on many features such

as the size and extent of the tumour and the time to recurrence.

BACK

|

Ovarian Cancers

Women who have a family

history of ovarian cancer are at an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. Women who have one first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or

sister) with ovarian cancer are at an increased risk of developing ovarian

cancer. This risk is higher in women who have one first-degree relative and one

second-degree relative (grandmother or aunt) with ovarian cancer. This risk is

even higher in women who have two or more first-degree relatives with ovarian

cancer. Some ovarian cancers are caused by inherited gene mutations (changes).

Women who have one first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or

sister) with ovarian cancer are at an increased risk of developing ovarian

cancer. This risk is higher in women who have one first-degree relative and one

second-degree relative (grandmother or aunt) with ovarian cancer. This risk is

even higher in women who have two or more first-degree relatives with ovarian

cancer. Some ovarian cancers are caused by inherited gene mutations (changes).Ovarian cancer is a disease

produced by the rapid growth and division of cells within one or both

ovaries—reproductive glands in which the ova, or eggs, and the female sex

hormones are made. The ovaries contain cells that, under normal circumstances,

reproduce to maintain tissue health. When growth control is lost and cells

divide too much and too fast, a cellular mass is formed. If the tumour is

confined to a few cell layers, for example, surface cells,

and it does not

invade surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered benign. If the tumour

spreads to surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered malignant, or

cancerous. When cancerous cells break away from the original tumour, travel

through the blood or lymphatic vessels, and grow within other parts of the body,

the process is known as metastasis and it does not

invade surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered benign. If the tumour

spreads to surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered malignant, or

cancerous. When cancerous cells break away from the original tumour, travel

through the blood or lymphatic vessels, and grow within other parts of the body,

the process is known as metastasis

Many kinds of tumours can form in the ovaries. In fact, there are over 30

known histopathologic, or diseased tissue, types. Experts group ovarian cancers

within three major categories, according to the type of cells from which they

were formed.

- Epithelial cancers, which are the most common ovarian cancers, arise from

cells lining or covering the ovaries.

- Germ cell cancers start from germ cells (cells that are destined to form

eggs) within the ovaries.

- Sex cord, stromal cell cancers, begin in the cells that hold the ovaries

together and produce female hormones.

Incidence and Prevalence

Ovarian cancer is a disease that principally affects middle and upper-class

women in industrialized nations. It is uncommon in underdeveloped countries,

perhaps because of different dietary factors in these regions

It is estimated that approximately 30,000 new cases of ovarian cancer will be

diagnosed this year, with 15,000 women dying from this disease. Ovarian cancer

most frequently appears in women who are older than 60 (about 50% of patients

are over age 65), although it may occur in younger women who have a family

history of the disease. Ovarian cancer is responsible for 5% of all cancer

deaths among women.

There are marked differences in survival among patients with ovarian cancer,

depending on factors such as age, cancer stage, and tissue type. Younger

patients tend to fare better in all stages than do older patients, whereas race

does not play a factor, as it does in other cancers. Survival rates are similar

in black and white women.

Ovarian Anatomy

The ovaries are female reproductive organs that are akin to the testes in men.

They produce the ova (eggs) that, when fertilized, will develop into a foetus;

they also generate the female sex hormones oestrogen and progesterone. There are

two ovaries, each of which is located within the pelvic region beside the uterus

(womb).

Ovarian Structure

The ovaries are oval-shaped and are approximately 1 ½ inches in length. They are

pinkish-grey in colour and have an uneven surface. The ovaries are connected to

the uterus by the fallopian tubes, or oviducts, which carry the eggs into the

uterine cavity. Each ovary contains numerous Graafian follicles, egg-containing

tubes that grow and develop between puberty, sexual maturation, and menopause,

when the monthly menstrual cycle stops. When a woman is fertile, each month a

Graafian follicle travels to the surface of the ovary, bursts, and releases an

egg and its fluid contents into a fallopian tube.

The Graafian follicles are fixed in a network of supporting tissue (stroma)

and blood vessels. They are covered by a clear, smooth, plasma-like membrane

that develops from the peritoneum - lining of the abdominal cavity. Also within

the ovaries are small numbers of corpus lutea - the remains of Graafian

follicles that have released an egg and are in the process of being reabsorbed

by ovarian tissue. Each month the corpus luteum (the scar tissue of a Graafian

follicle) is responsible for the production of progesterone. Progesterone is the

pregnancy hormone that readies the lining of the uterus for the arrival of a

fertilized egg.

Ovarian Function

During the first half of a woman's menstrual cycle - about 2 weeks before

ovulation, an egg is released. The hypothalamus in the brain sends a hormonal

signal to the pituitary gland to release follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) into

the bloodstream. When the blood-borne FSH reaches the ovaries, it spurs the

Graafian follicles to grow and produce oestrogen. Additional oestrogen is made

by hormone-producing tissue within the stroma. One Graafian follicle in an ovary

begins to outgrow the other follicles while the eostrogen level is increasing.

Meanwhile, once the oestrogen level has peaked, the pituitary gland stops the

output of FSH and begins to release luteinizing hormone (LH). The LH causes the

Graafian follicle to bubble out on the outside of the ovary, burst, and eject

its egg into the fallopian tube. This process of ovulation occurs on or about

the 14th day of the menstrual cycle. The ovulated egg travels through the

fallopian tube for 5 to 7 days, after which it is released into the uterus.

Connective Tissue

The ovaries are held in place by bands of fibrous tissue known as ligaments. The

ligament of the ovary is a rounded cord that extends from the upper uterus to

the lower, inner region of the ovary. The fimbria ovarica are fringe-like

tissues that attach the ovaries to the fallopian tubes. The round ligaments are

two cords, 4 to 5 inches in length, that connect with layers of the broad

ligament (ligament that attaches to each side of the pelvic wall to support the

uterus) in front of and below the fallopian tubes.

Blood Vessels and Nerves

The ovarian arteries, which are offshoots of the abdominal aorta, furnish the

ovaries and fallopian tubes with blood. They enter the ovary via an attached

border, or hilus. The ovarian veins parallel the route of the arteries, forming

a tangled network in the broad ligament known as the pampiniform plexus.

The nerves that supply the ovaries are branches of the inferior hypogastric

nerve, the pelvic plexus (network), the ovarian plexus, and uterine nerves

within the fallopian tubes.

BACK

|

Sarcoma of the uterus

Sarcoma of the uterus, a very rare kind of cancer in women, is a disease

in which cancer cells start growing in the muscles or other supporting

tissues of the uterus. The uterus is the hollow, pear-shaped organ where a

baby grows. Sarcoma of the uterus is different from cancer of the

endometrium, a disease in which cancer cells start growing in the lining of

the uterus.

Women who have received therapy with high-dose x-rays (external-beam

radiation therapy) to their pelvis are at a higher risk to develop sarcoma

of the uterus. These x-rays are sometimes given to women to stop bleeding

from the uterus.

A doctor should be seen if there is bleeding after menopause (the time

when a woman no longer has menstrual periods) or bleeding that is not part

of menstrual periods.

Sarcoma of the uterus usually begins after menopause. If there are signs of cancer, a doctor will do certain tests to check for

cancer, usually beginning with an internal (pelvic) examination. During the

examination, the doctor will feel for any lumps or changes in the shapes of

the pelvic organs. The doctor may then do a Pap test, using a piece of

cotton, a small wooden stick, or brush to gently scrape the outside of the

cervix (the opening of the uterus) and the vagina to pick up cells. Because

sarcoma of the uterus begins inside, this cancer will not usually show up on

the Pap test. The doctor may also do a dilation and curettage (D & C) by

stretching the cervix and inserting a small, spoon-shaped instrument into

the uterus to remove pieces of the lining of the uterus. This tissue is then

checked under a microscope for cancer cells.

The prognosis (chance of recovery) and choice of treatment depend on the

stage of the sarcoma (whether it is just in the uterus or has spread to

other places), how fast the tumour cells are growing, and the patient’s

general state of health.

|

Stages of sarcoma of the uterusOnce sarcoma of the uterus has been found, more tests will be done to find

out if the cancer has spread from the uterus to other parts of the body

(staging). A doctor needs to know the stage of the disease to plan treatment.

The following stages are used for sarcoma of the uterus:

Stage I

Cancer is found only in the main part of the uterus (it is not found in the

cervix).

Stage II

Cancer cells have spread to the cervix.

Stage III

Cancer cells have spread outside the uterus but have not spread outside the

pelvis.

Stage IV

Cancer cells have spread beyond the pelvis, to other body parts, or into the

lining of the bladder (the sac that holds urine) or rectum.

Recurrent

Recurrent disease means that the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has

been treated.

How sarcoma of the uterus is treated

There are treatments for all patients with sarcoma of the uterus. Four kinds

of treatment are used:

- Surgery (taking out the cancer in an operation).

- Radiation therapy (using high-dose x-rays or other high-energy

rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors).

- Chemotherapy (using drugs to kill cancer cells).

- Hormone therapy (using female hormones to kill cancer cells).

Surgery is the most common treatment of sarcoma of the uterus. A doctor may

take out the cancer in an operation to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and

the ovaries, along with some lymph nodes in the pelvis and around the aorta (the

main vessel in which blood passes away from the heart). The operation is called

a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and

lymphadenectomy. (The lymph nodes are small bean-shaped structures that are

found throughout the body. They produce and store infection-fighting cells, but

may contain cancer cells.)

Radiation therapy uses x-rays or other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells

and shrink tumours. Radiation therapy for sarcoma of the uterus usually comes

from a machine outside the body (external radiation). Radiation may be used

alone or in addition to surgery.

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be taken by

pill, or it may be put into the body by a needle in a vein or a muscle.

Chemotherapy is called a systemic treatment because the drugs enter the

bloodstream, travel through the body, and can kill cancer cells outside the

uterus.

Hormone therapy uses female hormones, usually taken by pill, to kill cancer

cells.

Treatment by stage

Treatment of sarcoma of the uterus depends on the stage and cell type of the

disease, and the patient’s age and overall condition. Standard treatment may be considered because of its effectiveness in patients

in past studies, or participation in a clinical trial may be considered. Not all

patients are cured with standard therapy and some standard treatments may have

more side effects than are desired. For these reasons, clinical trials are

designed to find better ways to treat cancer patients and are based on the most

up-to-date information.

Stage I Uterine Sarcoma

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and the ovaries,

and some of the lymph nodes in the pelvis and abdomen (total abdominal

hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymph node dissection)

- Total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy,

and lymph node dissection, followed by radiation therapy to the pelvis.

- Surgery followed by chemotherapy.

- Surgery followed by radiation therapy.

Stage II Uterine Sarcoma

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and the ovaries,

and some of the lymph nodes in the pelvis and abdomen (total abdominal

hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymph node dissection)

- Total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy,

and lymph node dissection, followed by radiation therapy to the pelvis.

- Surgery followed by chemotherapy.

- Surgery followed by radiation therapy.

Stage III Uterine Sarcoma

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and the ovaries,

and some of the lymph nodes in the pelvis and abdomen (total abdominal

hysterectomy bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and lymph node dissection).

Doctors will also try to remove as much of the cancer that has spread to

nearby tissues as possible.

- Total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy,

and lymph node dissection, followed by radiation therapy to the pelvis.

- Surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Stage IV Uterine Sarcoma

Treatment will usually be a clinical trial using chemotherapy.

Recurrent Uterine Sarcoma

If the cancer has come back (recurred), treatment may be one of the

following:

- Clinical trials of chemotherapy or hormone therapy.

- External radiation therapy to relieve symptoms such as pain,

nausea, or abnormal bowel functions.

BACK

|

| Vaginal Cancer

Cancer of the vagina, a rare kind of cancer in women, is a disease in which

cancer (malignant) cells are found in the tissues of the vagina. The vagina is

the passageway through which fluid passes out of the body during menstrual

periods and through which a woman has babies. It is also called the "birth

canal." The vagina connects the cervix (the opening of the womb or uterus) and

the vulva (the folds of skin around the opening to the vagina).

There are two types of cancer of the vagina: squamous cell cancer (squamous

carcinoma) and adenocarcinoma. Squamous carcinoma is usually found in women

between the ages of 60 and 80. Adenocarcinoma is more often found in women

between the ages of 12 and 30.

Young women whose mothers took DES (diethylstilbestrol) are at risk

of

getting tumours in their vaginas. Some of them get a rare form of cancer called

clear cell adenocarcinoma. The drug DES was given to pregnant women between 1945

and 1970 to keep them from losing their babies (miscarriage).

A doctor should be seen if there are any of the following:

- Bleeding or discharge not related to menstrual periods.

- Difficult or painful urination.

- Pain during intercourse or in the pelvic area.

- Also, there is still a chance of developing vaginal cancer in

women who have had a hysterectomy.

A doctor may use several tests to see if there is cancer. The doctor will

usually begin by giving the patient an internal (pelvic) examination. The doctor

will feel for lumps and will then do a Pap smear. Using a piece of cotton, a

brush, or a small wooden stick, the doctor will gently scrape the outside of the

cervix and vagina in order to pick up cells. Some pressure may be felt, but

usually with no pain.

If cells that are not normal are found, the doctor will need to cut a small

sample of tissue (called a biopsy) out of the vagina and look at it under a

microscope to see if there are any cancer cells. The doctor should look not only

at the vagina, but also at the other organs in the pelvis to see where the

cancer started and where it may have spread. The doctor may take an x-ray of the

chest to make sure the cancer has not spread to the lungs.

The chance of recovery (prognosis) and choice of treatment depend on the

stage of the cancer (whether it is just in the vagina or has spread to other

places) and the patient's general state of health.

Stages of cancer of the vagina

Once cancer of the vagina has been found (diagnosed), more tests will be done

to find out if the cancer has spread from the vagina to other parts of the body

(staging). A doctor needs to know the stage of the disease to plan treatment.

The following stages are used for cancer of the vagina:

Stage 0 or carcinoma in situ

Stage 0 cancer of the vagina is a very early cancer. The cancer is found

inside the vagina only and is in only a few layers of cells.

Stage I

Cancer is found in the vagina, but has not spread outside of it.

Stage II

Cancer has spread to the tissues just outside the vagina, but has not gone to

the bones of the pelvis.

Stage III

Cancer has spread to the bones of the pelvis. Cancer cells may also have

spread to other organs and the lymph nodes in the pelvis. (Lymph nodes are small

bean-shaped structures that are found throughout the body. They produce and

store cells that fight infection.)

Stage IVA

Cancer has spread into the bladder or rectum.

Stage IVB

Cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs.

Recurrent

Recurrent disease means that the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has

been treated. It may come back in the vagina or in another place.

How cancer of the vagina is treated

Treatments are available for all patients with cancer of the vagina. There

are three kinds of treatment:

- Surgery (taking out the cancer in an operation).

- Radiation therapy (using high-dose x-rays or other high-energy

rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumours).

- Chemotherapy (using drugs to kill cancer cells).

Surgery is the most common treatment of all stages of cancer of the vagina. A

doctor may take out the cancer using one of the following:

- Laser surgery uses a

narrow beam of light to kill cancer cells and is useful for stage 0 cancer

- Wide local excision takes out the cancer and some of the

tissue around it. A patient may need to have skin taken from another part of

the body (grafted) to repair the vagina after the cancer has been taken out.

- An operation in which the vagina is removed (vaginectomy) is

sometimes done. When the cancer has spread outside the vagina, vaginectomy may

be combined with surgery to take out the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian

tubes (radical hysterectomy). During these operations, lymph nodes in the

pelvis may also be removed (lymph node dissection)

- If the cancer has spread outside the vagina and the other

female organs, the doctor may take out the lower colon, rectum, or bladder

(depending on where the cancer has spread) along with the cervix, uterus, and

vagina (exenteration)

- A patient may need skin grafts and plastic surgery to make an

artificial vagina after these operations.

Radiation therapy uses x-rays or other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells

and shrink tumours. Radiation may come from a machine outside the body (external

radiation) or from putting materials that produce radiation (radioisotopes)

through thin plastic tubes into the area where the cancer cells are found

(internal radiation). Radiation may be used alone or after surgery.

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be taken by

pill, or it may be put into the body by a needle in a vein. Chemotherapy is

called a systemic treatment because the drugs enter the bloodstream, travel

through the body, and can kill cancer cells outside the vagina. In treating

vaginal cancer, chemotherapy may also be put directly into the vagina itself,

which is called intra-vaginal chemotherapy.

Stage 0 Vaginal Cancer

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove all or part of the vagina (vaginectomy).

This may be followed by skin grafting to repair damage done to the vagina.

- Internal radiation therapy.

- Laser surgery.

- Intravaginal chemotherapy

Stage I Vaginal Cancer

Treatment of stage I cancer of the vagina depends on whether a patient has

squamous cell cancer or adenocarcinoma.

If squamous cancer is found, treatment may be one of the following:

- Internal radiation therapy with or without external beam

radiation therapy.

- Wide local excision. This may be followed by the rebuilding of

the vagina. Radiation therapy following surgery may also be performed in some

cases.

- Surgery to remove the vagina with or without lymph nodes in

the pelvic area (vaginectomy and lymph node dissection).

If adenocarcinoma is found, treatment may be one of the following:

- Surgery to remove the vagina (vaginectomy) and the uterus,

ovaries, and fallopian tubes (hysterectomy). The lymph nodes in the pelvis are

also removed (lymph node dissection). This may be followed by the rebuilding

of the vagina. Radiation therapy following surgery may also be performed in

some cases.

- Internal radiation therapy with or without external beam

radiation therapy.

- In selected patients, wide local excision and removal of some

of the lymph nodes in the pelvis followed by internal radiation

Stage II Vaginal Cancer

Treatment of stage II cancer of the vagina is the same whether a patient has

squamous cell cancer or adenocarcinoma.

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Combined internal and external radiation therapy.

- Surgery, which may be followed by radiation therapy.

Stage III Vaginal Cancer

Treatment of stage III cancer of the vagina is the same whether a patient has

squamous cell cancer or adenocarcinoma.

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Combined internal and external radiation therapy.

- Surgery may sometimes be combined with radiation therapy.

Stage IVA Vaginal Cancer

Treatment of stage IVA cancer of the vagina is the same whether a patient has

squamous cell cancer or adenocarcinoma.

Treatment may be one of the following:

- Combined internal and external radiation therapy.

- Surgery may sometimes be combined with radiation therapy

Stage IVB Vaginal Cancer

If stage IVB cancer of the vagina is found, treatment may be radiation to

relieve symptoms such as pain, nausea, vomiting, or abnormal bowel function.

Chemotherapy may also be performed. A patient may also choose to participate in

a clinical trial.

Recurrent Vaginal Cancer

If the cancer has come back (recurred) and spread past the female organs, a

doctor may take out the cervix, uterus, lower colon, rectum, or bladder (exenteration),

depending on where the cancer has spread. The doctor may give the patient

radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

A patient may also choose to participate in a clinical trial of chemotherapy

or radiation therapy.

BACK

|

| Cancer of the

Vulva

Cancer of the vulva, a rare kind of cancer in women, is a disease in which

cancer (malignant) cells are found in the vulva. The vulva is the outer part of

a woman’s vagina. The vagina is the passage between the uterus (the hollow,

pear-shaped organ where a baby grows) and the outside of the body. It is also

called the birth canal.

Most women with cancer of the vulva are over age 50. However, it is becoming

more common in women under age 40. Women who have constant itching and changes

in the colour and the way the vulva looks are at a high risk to get cancer of

the vulva. A doctor should be seen if there is bleeding or discharge not related

to menstruation (periods), severe burning/itching or pain in the vulva, or if

the skin of the vulva looks white and feels rough.

If there are symptoms, a doctor may do certain tests to see if there is

cancer, usually beginning by looking at the vulva and feeling for any lumps. The

doctor may then go on to cut out a small piece of tissue (called a biopsy) from

the vulva and look at it under a microscope. A patient will be given some

medicine to numb the area when the biopsy is done. Some pressure may be felt,

but usually with no pain. This test is often done in a doctor’s office.

The chance of recovery (prognosis) and choice of treatment depend on the

stage of the cancer (whether it is just in the vulva or has spread to other

places) and the patient’s general state of health.

Stages of cancer of the vulva

Once cancer of the vulva is diagnosed, more tests will be done to find out if

the cancer has spread from the vulva to other parts of the body (staging). A

doctor needs to know the stage of the disease to plan treatment. The following

stages are used for cancer of the vulva:

Stage 0 or carcinoma in situ

Stage 0 cancer of the vulva is a very early cancer. The cancer is found in

the vulva only and is only in the surface of the skin.

Stage I

Cancer is found only in the vulva and/or the space between the opening of the

rectum and the vagina (perineum). The tumour is 2 centimetres (about 1 inch) or

less in size.

Stage II

Cancer is found in the vulva and/or the space between the opening of the

rectum and the vagina (perineum), and the tumour is larger than 2 centimetres

(larger than 1 inch).

Stage III

Cancer is found in the vulva and/or perineum and has spread to nearby tissues

such as the lower part of the urethra (the tube through which urine passes), the

vagina, the anus (the opening of the rectum), and/or has spread to nearby lymph

nodes. (Lymph nodes are small bean-shaped structures that are found throughout

the body. They produce and store infection-fighting cells.)

Stage IV

Cancer has spread beyond the urethra, vagina, and anus into the lining of the

bladder (the sac that holds urine) and the bowel (intestine); or, it may have

spread to the lymph nodes in the pelvis or to other parts of the body.

Recurrent

Recurrent disease means that the cancer has come back (recurred) after it has

been treated. It may come back in the vulva or another place.

How cancer of the vulva is treated

There are treatments for all patients with cancer of the vulva. Three kinds

of treatment are used:

- Surgery (taking out the cancer in an operation).

- Radiation therapy (using high-dose x-rays or other high-energy

rays to kill cancer cells).

- Chemotherapy (using drugs to kill cancer cells).

Surgery is the most common treatment of cancer of the vulva. A doctor may

take out the cancer using one of the following operations:

- Wide local excision takes

out the cancer and some of the normal tissue around the cancer

- Radical local excision

takes out the cancer and a larger portion of normal tissue around the

cancer. Lymph nodes may also be removed

- Laser surgery uses a

narrow beam of light to remove cancer cells

- Skinning vulvectomy takes

out only the skin of the vulva that contains the cancer

- Simple vulvectomy takes

out the entire vulva, but no lymph nodes

- Partial vulvectomy takes

out less than the entire vulva

- Radical vulvectomy takes

out the entire vulva. The lymph nodes around it are usually removed as well

- If the cancer has spread outside the vulva and the other

female organs, the doctor may take out the lower colon, rectum, or bladder

(depending on where the cancer has spread) along with the cervix, uterus, and

vagina (pelvic exenteration).

A patient may need to have skin from another part of the body added (grafted)

and plastic surgery to make an artificial vulva or vagina after these

operations.

Radiation therapy uses x-rays or other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells

and shrink tumours. Radiation may come from a machine outside the body (external

radiation) or from putting materials that contain radiation through thin plastic

tubes into the area where the cancer cells are found (internal radiation).

Radiation may be used alone or before or after surgery.

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Drugs may be given by mouth, or

they may be put into the body by a needle in the vein or muscle. Chemotherapy is

called systemic treatment because the drug enters the bloodstream, travels

through the body, and can kill cancer cells throughout the body.

BACK

HELPLINES

Jo's Trust - Fighting Cervical Cancer

Pamela Morton

Tel:01327 361787

web site

www.jotrust.co.uk email

pamela@jotrust.co.uk

Ovacome

(for all those involved in ovarian cancer, inc. patients, carers, families etc.)

St Bartholomew's Hospital,

West Smithfield,

London EC1A 7BE

Tel 020 7600 5141 (Monday to Friday 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.)

web site

www.ovacome.org.uk

email

ovacome@ovacome.org.uk

Gynae C (for women with any gynae

cancer, their partners, families & friends)

1 Bolingbroke Road,

Swindon,

SN2 2LB

01793 322005

www.communigate.co.uk/wilts/gynaec/index.phtml

email

gynae_c@yahoo.com

Amarant Trust (advice line for

women going through the menopause)

01293 413000 (Monday to Friday 11a.m. to 6 p.m.)

Radical Vulvectomy Support Group

01977 640 243 (highly confidential telephone support)

V.A.C.O. (Vulva Awareness Charity

Organisation)

Tel 0161 747 5911 (highly

confidential telephone support)

email

carol@jones5911.fsnet.co.uk

BACK |

Women who have one first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or

sister) with ovarian cancer are at an increased risk of developing ovarian

cancer. This risk is higher in women who have one first-degree relative and one

second-degree relative (grandmother or aunt) with ovarian cancer. This risk is

even higher in women who have two or more first-degree relatives with ovarian

cancer. Some ovarian cancers are caused by inherited gene mutations (changes).

Women who have one first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or

sister) with ovarian cancer are at an increased risk of developing ovarian

cancer. This risk is higher in women who have one first-degree relative and one

second-degree relative (grandmother or aunt) with ovarian cancer. This risk is

even higher in women who have two or more first-degree relatives with ovarian

cancer. Some ovarian cancers are caused by inherited gene mutations (changes).

Vaginal bleeding.

Vaginal bleeding.  Endometrial cancer is considered an oestrogen-dependent

disease. Oestrogen is a hormone that is secreted by the ovaries. It plays an

important role in the development of the female reproductive system and is

largely responsible for the physiologic changes that occur during menstruation,

puberty, and pregnancy. Progesterone is another hormone secreted by the ovaries

that plays an important role. Normally, both oestrogen and progesterone are

secreted in certain proportions. Chronic exposure to oestrogen, without the

accompanying balancing effects of progesterone, is considered the major risk

factor for endometrial cancer and may play a causal role in the development of

the disease.

Endometrial cancer is considered an oestrogen-dependent

disease. Oestrogen is a hormone that is secreted by the ovaries. It plays an

important role in the development of the female reproductive system and is

largely responsible for the physiologic changes that occur during menstruation,

puberty, and pregnancy. Progesterone is another hormone secreted by the ovaries

that plays an important role. Normally, both oestrogen and progesterone are

secreted in certain proportions. Chronic exposure to oestrogen, without the

accompanying balancing effects of progesterone, is considered the major risk

factor for endometrial cancer and may play a causal role in the development of

the disease.

The uterus has a flat, inner surface and is covered with tall,

columnar epithelial cells. There are pits in the surface that lead down into

uterine glands. The columnar cells, the pits, and the connective tissue and

blood vessels that surround the glands are all part of the endometrium. The

endometrium undergoes dramatic changes during a woman's menstrual cycle. During

the luteal phase, for example, the two-week period just before a woman bleeds,

the endometrium is thick, its epithelial cells are enlarged, the glands bulging,

and the arteries swollen. At menstruation, the arteries break, the epithelial

cells die, and the endometrium, in effect, sheds. Following menstruation, during

the follicular phase, the endometrium regenerates. The changing thickness of the

endometrium is highly dependent on the secretion of oestrogen and progesterone.

Oestrogen causes cellular growth and is an important component of the

rebuilding, follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone is secreted

during the later, thick-walled luteal phase, and it balances out the effects of

the oestrogen. Abnormal growth of endometrial cells (whether cancerous or not)

and endometrial cancer are believed to be due to chronic exposure to too much

oestrogen without the balancing effect of progesterone.

The uterus has a flat, inner surface and is covered with tall,

columnar epithelial cells. There are pits in the surface that lead down into

uterine glands. The columnar cells, the pits, and the connective tissue and

blood vessels that surround the glands are all part of the endometrium. The

endometrium undergoes dramatic changes during a woman's menstrual cycle. During

the luteal phase, for example, the two-week period just before a woman bleeds,

the endometrium is thick, its epithelial cells are enlarged, the glands bulging,

and the arteries swollen. At menstruation, the arteries break, the epithelial

cells die, and the endometrium, in effect, sheds. Following menstruation, during

the follicular phase, the endometrium regenerates. The changing thickness of the

endometrium is highly dependent on the secretion of oestrogen and progesterone.

Oestrogen causes cellular growth and is an important component of the

rebuilding, follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone is secreted

during the later, thick-walled luteal phase, and it balances out the effects of

the oestrogen. Abnormal growth of endometrial cells (whether cancerous or not)

and endometrial cancer are believed to be due to chronic exposure to too much

oestrogen without the balancing effect of progesterone. and it does not

invade surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered benign. If the tumour

spreads to surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered malignant, or

cancerous. When cancerous cells break away from the original tumour, travel

through the blood or lymphatic vessels, and grow within other parts of the body,

the process is known as metastasis

and it does not

invade surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered benign. If the tumour

spreads to surrounding tissues or organs, it is considered malignant, or

cancerous. When cancerous cells break away from the original tumour, travel

through the blood or lymphatic vessels, and grow within other parts of the body,

the process is known as metastasis