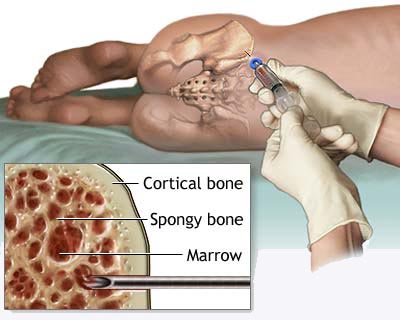

- Bone marrow sample

- Philadelphia chromosome

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia

Adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is a type of cancer

in which the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell)

In ALL, too many stem cells develop into a type of white blood called lymphocytes. These lymphocytes may also be called lymphoblasts or leukaemic cells. There are 3 types of lymphocytes:

The lymphocytes are not able to fight infection very well.

Also, as the number of lymphocytes increases in the blood and bone marrow, there

is less room for healthy white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets. This

may cause infection, anaemia, and easy bleeding. The cancer can also spread to

the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord).

Possible signs include fever, feeling tired, and easy bruising or bleeding. The early signs may be similar to the flu or other common diseases. A doctor should be consulted if any of the following problems occur:

These and other symptoms may be caused by adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia or by other conditions. Tests that examine the blood and bone marrow are used to detect (find) and diagnose. The following tests and procedures may be used:

Bone marrow biopsy and aspiration: The removal of a small

piece of bone and bone marrow by inserting a needle into the hipbone or

breastbone. A pathologist views the samples under a microscope to look for

abnormal cells. Bone marrow biopsy and aspiration: The removal of a small

piece of bone and bone marrow by inserting a needle into the hipbone or

breastbone. A pathologist views the samples under a microscope to look for

abnormal cells.Cytogenetic analysis: A test in which the cells in a sample of blood or bone marrow are looked at under a microscope to find out if there are certain changes in the chromosomes in the lymphocytes. For example, sometimes in ALL, part of one chromosome is moved to another chromosome. This is called the Philadelphia chromosome.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and

treatment options.

Stages of Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia

|

|

Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia

Because CML develops slowly, it is difficult to detect in its

early stages. Sometimes it is discovered only when a blood test is done for

another reason. The symptoms of CML are often vague and non-specific and are caused by the increased number of abnormal white blood cells in the bone marrow and the reduced number of normal blood cells:

If you have any of the above symptoms, it is important to see your doctor, but remember, they are common to many illnesses other than chronic myeloid leukaemia. Phases of CML Chronic myeloid leukaemia is a blood and bone marrow disease that develops slowly. It has three phases. The phase is determined by the number of blast cells in the blood and bone marrow and the severity of symptoms. The chronic phase

|

|

Chronic

Lymphocytic Leukaemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is a cancer of the white blood

cells called lymphocytes. It is the commonest type of leukaemia. Chronic

lymphocytic leukaemia mainly affects older people and is rare in people under

age 40

Blood cells are normally produced in a controlled way, but in leukaemia, the process gets out of control. The lymphocytes multiply too quickly and live too long, so there are too many of them circulating in the blood. These leukaemic lymphocytes look normal, but they are not fully developed and do not work properly. Over a period of time these abnormal cells replace the normal white cells, red cells and platelets in the bone marrow. The disease usually develops slowly and many people with

chronic lymphocytic leukaemia do not need treatment for months or years. Some

people need treatment straight away. What causes chronic lymphocytic leukaemia?

The cause of CLL is not known, but research is going on all the

time to try to find out. Like other What are the symptoms of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia?

Because the disease develops slowly, it is difficult to detect

in its early stages. Some people have no symptoms and the disease may be

discovered only when a blood test is taken for a different reason.

The symptoms of CLL can include:

People with CLL are more likely to get infections because they have a shortage of healthy white blood cells to fight off bacteria and viruses. A lack of red blood cells (anaemia) causes tiredness and sometimes breathlessness. There are not enough red blood cells because the abnormal lymphocytes are taking up too much space in the bone marrow. Your platelet count may be low too, for the same reason. This can cause unexplained bruising or bleeding, such as nosebleeds. Abnormal lymphocytes may collect in lymph glands and cause swellings in your neck, armpits or groin. The swollen lymph glands are usually painless but may be sore. Your spleen may become enlarged and cause a tender lump in the upper left-hand side of your abdomen. Sweating or a high temperature at night can also sometimes

occur. Some people lose weight. How it is diagnosed?

Your GP will examine you and carry out a blood test. If this

blood test shows that your blood cell counts are abnormal, your GP will then

refer you to a hospital specialist, called a haematologist, for specialist

advice and treatment.

The doctor at the hospital will take your full medical history and do a physical examination, checking for any enlargement of the lymph nodes, spleen or liver. You will also have further blood tests to examine your blood cell counts in more detail. If your blood tests show leukaemia cells, you may need to have a bone marrow test to be sure of the diagnosis and so that the best treatment can be planned for you. Bone marrow testA small sample (biopsy) of bone marrow is taken from the

hipbone (pelvis) or the breast bone (sternum), and looked at under the

microscope to see if it contains any abnormal white blood cells. The doctor

will be able to tell which type of leukaemia it is by identifying the type of

abnormal white cell.

The bone marrow sample is taken under a local anaesthetic. You are given an injection to numb the area and a needle is pushed gently through the skin into the bone. A sample of the marrow is then drawn into a syringe. Usually a small core of marrow is needed (a trephine biopsy) and this takes a few minutes. The test can be done on the ward, or in the outpatients department. The procedure can be painful, but only takes about 15 minutes. You may be offered a mild sedative to reduce any pain or discomfort during the test. Types of treatment?

Some people with stage A chronic lymphocytic leukaemia never

have treatment if their illness is not causing any symptoms and is

progressing only very slowly. There is no advantage to having treatment if

your CLL is at an early stage, unless you have symptoms. But it is still

important to attend for regular check-ups and blood counts, as this is the

main way your doctor has of monitoring the progress of the leukaemia.

Treatment is only started if and when the symptoms become troublesome.

If treatment is necessary, you will be started on medication either as tablets, or by injection into a vein (intravenous chemotherapy). Your specialist will be able to tell what is the best form of treatment for you by monitoring the level of cells in your blood. Usually, people with CLL begin on chemotherapy tablets and may then have chemotherapy by injection if their symptoms do not continue to improve. Steroids may be given along with the chemotherapy. This is to help the chemotherapy work more effectively. Monoclonal antibodies such as alemtuzumab and rituximab may be used to treat CLL. These can recognise CLL cells and destroy them, while having little effect on normal cells. Some younger patients are offered treatment with high dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplant. This treatment is experimental, but may result in a long period with no active disease (remission) for some people. Radiotherapy is sometimes used to treat bulky enlarged lymph nodes, or enlarged spleen. Alternatively, an enlarged spleen may be removed surgically (splenectomy).

|

Hairy Cell Leukaemia

|

|

Acute Myeloid Leukaemia

Acute myeloid leukaemia is a

rare type of cancer, affecting approximately 2,000 adults and 50 children per

year in the UK.

Leukaemia is a cancer of the white blood cells (phagocytes) Acute myeloid leukaemia is an overproduction of immature myeloid white blood cells. The immature cells are sometimes referred to as blast cells. Normally, white blood cells repair and reproduce themselves in an orderly and controlled way. In leukaemia, however, the process gets out of control and the cells continue to divide, but do not mature. These immature dividing cells fill up the bone marrow and prevent it from making healthy blood cells. As the leukaemia cells do not mature, they cannot work properly, which leads to an increased risk of infection. As the bone marrow cannot make enough healthy red blood cells and platelets, symptoms such as anaemia and bruising also occur. Acute myeloid leukaemia can affect adults of all ages, but is more common in older age groups. It is rare in people under 20. What are the causes of acute

myeloblastic leukaemia?

|